Saturday Newsletter: May 21, 2022

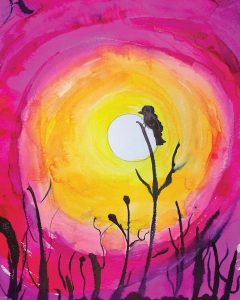

A note from Emma Letters crash around me like waves in a storm… In this poem, Lilly Davatzes is clearly...

Read More →

Read More →