The hot July sun beat its fiery rays down on the heads of the slaves working in the shelterless Carolina cotton field. Tall, twelve-year-old Curtis, dragging his cotton bag behind him, paused to steal a moment to soothe his aching back. Straightening up, he winced as his back stretched. His hands, rough and scarred from picking cotton day after day, twitched at his decrepit straw hat. Glancing over the field, he spotted the Big House, standing out starkly against the darker forest behind it. “You! Boy! Keep working!” The order was shouted out in a harsh, thick voice from behind Curtis.

Resisting the urge to shout back, “My name’s not Boy! It’s Curtis!” he bent over his work once more. Curtis what? he wondered, disgusted, to himself. It didn’t really matter, of course, but still, the lack of a last name galled him. Stop worrying about it, he told himself. No one even calls you by your first name, let alone an appendage like a last name. Curtis couldn’t forget it though. He sometimes wondered where his parents were. All he knew was that he had been born in the hold of a slave ship somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean. He had no memory of his mother or father, let alone a last name. Oh well. Who needs a last name? he tried to satiate himself. It didn’t work.

“Sing!” the overseer ordered roughly. “Sing and be cheerful!” If slaves were quiet, overseers took it for a sign that they were plotting escape. Singing was a popular way to keep them “happy.” One of the slaves struck up:

Gonna jump down, turn around, pick a bale o’ cotton,

Gonna jump down, turn around, pick a bale a day.

Oh, lawdy, pick a bale o’ cotton, oh, lawdy, pick a bale a day.

Gonna picka, picka, picka, picka, picka bale o’ cotton…

The overseer smiled at the swingy tune. Curtis scowled again.

That night, in the hut he shared with several other slaves, Curtis listened to the talk of Harriet Tubman. Most slaves called her Moses, after the way she freed slaves, like Moses had freed the Israelites. She had been to Canada already, but she came back to bring other slaves out of “Egypt.”

“They say she’s headed this way. If she comes to us, I mean to go. I’m sick of slavery.” A young black man tossed a stick into the fire. “I’m ready to ride the railroad to freedom.”

Me too, thought Curtis, sitting in his dark corner, listening, but unwilling to join the gossip. But will “Moses” ever come?

* * *

One week later, as the slaves sweated in the fields, Curtis caught the sound of someone singing. The song almost seemed to be coming from the woods beside the field. He knew the words. They were part of a popular slave hymn:

I looked over Jordan, and what did I see,

Comin’ for to carry me home?

A band of angels coming after me

Comin’ for to carry me home.

Swing low, sweet chariot, comin’ for to carry me home…

That’s odd, Curtis thought. Why would someone be singing that song on a weekday?

Then a faint memory flashed across his mind. Hadn’t he heard that slave rescuers sang that song to let other slaves know that it was time to escape? It had to be Harriet. Curtis began to sing the words too. Soon other voices joined in. The others knew; tonight was their escape. Curtis thought about escape for the rest of the day. Could he make it? Was slavery really worse than the unknown? Doubts assailed him. A moment later, hearing the crack of the overseer’s whip, Curtis glanced up. He glimpsed the unfortunate slave’s face twist in pain. In that moment, Curtis knew he had to go. Anything was better than slavery.

That night, five of the slaves, three men, a woman, and Curtis, packed their few belongings. Stealing as softly from the little quarter as possible, the five walked towards the woods. They would have to pass the Big House, where lights still blazed, to reach temporary safety. Curtis was almost having second thoughts again. If they were caught, they would be flogged and probably sold down south. The thought chilled his blood. There were such stories about the South… Curtis, clenching his teeth, forced himself to keep walking. I can’t endure anymore. I don’t care what they do to me, he told himself. Still, he glanced back fearfully as he slunk along behind the others. There. It was past.

Once in the woods, they were able to breathe more freely. Uncertain what to do, they halted. After a few moments, an owl called softly, and a figure glided out to them. Even in the dim light, Curtis was able to recognize Harriet Tubman from the posters he had seen of her. With her were six other slaves from a neighboring plantation.

“By dawn, they’ll have discovered our absence. We must put as much distance between ourselves and them as possible,” Harriet said, as she counted noses.

They started the long hike. The whole journey seemed odd and dreamlike to Curtis. The only noises were noises they themselves made. Harriet led her Israelites to a creek. “We’ve got to throw the dogs off the scent, so we’ll walk in the stream,” she explained, stepping into the chill water. The slaves followed her lead. Curtis shuddered as the water closed around his ankles. When they could finally climb out of the stream, Curtis could hardly feel his feet. Still they kept on. At last they came to a road. Here they could travel more quickly. The numb feeling had moved on up Curtis’s legs by the time when, at dawn, Harriet led them into a barn at a little distance from the road. The slaves collapsed, exhausted, on the warm hay, too tired even to worry about whether it was safe.

All the next day, the slaves rested in the barn, eating food that was brought out to them. The Quaker couple who owned the barn hated slavery and often helped Harriet bring her slaves through. That night, the man came and hitched his horses to the wagon. As he handed the reins to Harriet, Curtis stepped forward.

“You haven’t seen anyone who looked anything like me come through, have you, sir?” he asked hopefully, wondering if maybe, just maybe, his father had ever come through the railroad. The man stroked his beard thoughtfully.

“Come to think of it, there was a man who looked something like you. What’s your name?”

Curtis told him, hoping against hope.

“A man looking something like you passed through here not more’n a month ago. His name was Curtis too. I called him to mind the moment I saw you.” Curtis was overjoyed as he climbed into the wagon. Was his father on the road to freedom too? Maybe he could catch up with him! Curtis fell asleep with new hope burning in him.

* * *

For three weeks, the little band traveled, resting during the day and following the North Star by night. Slowly but surely, the slaves were nearing Canada and freedom. But Curtis had no further news of his father. Every night he whispered a prayer for safety. They had almost been caught several times.

At last, Harriet communicated that the next morning, they would cross by train into Canada. Curtis was glad to be at last at the end of the trail; he wondered if perhaps his father had made it too. As he lay down in the darkness, the cold northern wind sweeping among the trees, he glanced up at the stars. My Last night of slavery and fear. Curtis fell asleep thinking, Tomorrow.

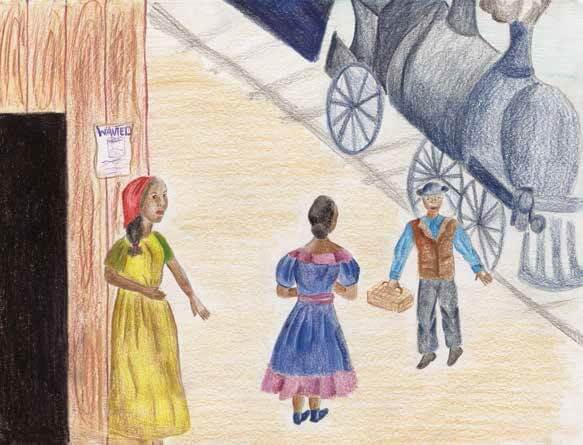

The next morning, when the group reached the train station, Harriet went inside to get tickets. Curtis was lounging on the bench outside with the others when he suddenly caught sight of a poster pinned up on the wall. He carefully spelled out the top lines:

WANTED: My black boy, Curtis. Said boy 12 years of age, hands scarred from cotton picking. Ran away from the subscriber 26 of July, 1832. $1000 reward for his capture, or satisfactory proof that he is dead.

Curtis felt sick. All this way and now this. No. He wasn’t going back. Curtis noticed two rather rough-looking men eyeing him thoughtfully. Fortunately, Harriet appeared with the tickets. Whispering his fears to her, Curtis pointed out the poster and the men. She nodded, and led him and Eva into an old, broken-down building. Digging into her pack, she handed each of them a new suit of clothes.

A few moments later, Curtis boarded the train that would carry him to freedom in Canada. He was dressed like a white boy now, not a ragged slave. Over one arm, he bore a seeming picnic basket. Turning, he called, “Come on, Mother! I can’t wait!” Eva smiled and hurried after him. One at a time, the slaves boarded. Curtis smirked. He’d walked right by those men. He slid into a window seat. All thought of his father almost vanished in the surge of adrenaline that shot through him. He was almost there! The whole way he could hardly hold still.

As the train neared the destination, Harriet called, “Come look out the window!” Curtis and the others managed to reach the windows and gasped at what they saw. Down far below, a huge waterfall sparkled in the sun, springing down from the heights. It’s free, like me! Exulted Curtis, staring in wonder at the gleaming water. An eagle soared over the water, screaming its harsh cry. A few moments later, the train pulled into the Canadian station.

As Curtis stepped out into the bracing air, he felt as though he would fly. The other slaves looked as he felt. Several passengers came up to shake hands and congratulate the now free men and women. A tall black man, buying a newspaper at a stand, heard the commotion and came over to add to it.

Why does be look familiar? Thought Curtis, staring at his face. “What is your name, sir?” he asked, touching the man’s sleeve. The man looked down at the boy for a moment.

“My first name is Curtis; why do you ask?” Curtis bypassed the question.

“Did you ever have a son called Curtis too, sir?” he asked, almost fearfully.

“Yes, I did… long ago. Have you seen him? Is he on the way to freedom too?” The man looked anxiously down into Curtis’s face. Curtis didn’t wait to hear the rest.

“Father! Father, don’t you know me? I’m Curtis!” The man looked puzzled, then looking at the boy once more, exclaimed in delight.

“You have your mother’s eyes, son!” he exclaimed.

“Where is Mother? Is she free too?” Curtis asked anxiously.

“Yes, Curtis. I wouldn’t have left without her, so she came with me. You’ll see her at the house. Come on!”

As father and son walked towards the small house a short distance from the station, a thought struck Curtis.

“Father, what is our last name? I’ve always wondered.”

His father answered, “Well, Curtis, when we came to this free country a month ago, we decided to take a new name because we’re no longer slaves. Our new last name is Freedom.”

Slowly a smile broke out on Curtis’s face. Freedom, he repeated to himself. Curtis Freedom.