The boat thrummed, vibrated for a few seconds, then stopped completely. “All right! All right! Everybody out! Everybody out!” yelled the driver. The whole scene made me think of some classical book or movie. But I liked it. It made me think of how much I loved camp last year—how excited I’d been for months leading up to now to go back.

I shoved the little sliver of homesickness that was already crowding into my throat and grinned. Things were starting to look familiar.

There were hills covered in tiny dots of brownish-gray that would be our cabins. There was a colorful, big dining hall, big enough to feed eighty kids three times a day, with signs all over it that said Recycle or Camp Three Rivers 1990. And the counselors were lined up on the dock, ready to meet and greet us, ready to attempt to impress our parents. All of them wore T-shirts that said Camp Three Rivers on them in big blue block letters.

Counselors. Last year I’d had the perfect counselor. Pretty. Young. Sweet. Smart, but not nerdy. Cool, but not stereotypical. I hoped for her. I prayed for her, despite my not being religious. I…

“Zoe? Are… are you Zoe?” asked a voice, rapidly cutting off my stream of reminiscence. I looked up. It was a counselor. She was on the chubby side, smiling, and young. Looked nice. I nodded.

“I’m Lyla,” she smiled-said. You know what I mean. When people say something, but you could really tell what they’re saying even if they weren’t saying it. Only people with big smiles can do this. Definitely not me.

“It’s great to meet you,” Lyla said. “I’ll be your counselor this year!”

I had no idea what to say. It’s not like, in that moment, I really could’ve said anything. I managed a weak smile.

“Your cabin will be Heron Hill, and your junior counselor will be Emma,” she went on. “I’m so so glad to meet you! This’ll be the best session! Ever!”

The cabin—my cabin—was small. Really small. I eyed my bed—the only bed left unoccupied. I eyed the kids playing outside. I looked up at my parents, and suddenly what used to be only a sliver of homesickness became a small, heavy coin, pushing, pushing, pushing me to beg my parents to take me back home.

In five minutes, I thought, they’ll be gone. Gone—for twelve days! Twelve days with no Nicky to toss a ball with, no Dad to embarrass me in the supermarket, no Mom to brush my hair even when I don’t want her to…

After my bed had been set up, and the goodbyes had been said, and I’d seen with my own eyes my parents walking down the steps and onto the boat, I stood there, perplexed, almost. I sat on my bunk and waited for the dinner bell to ring. The food was one of the elements at Camp Three Rivers that could never fail. It was always the same delicious, kid-friendly, home-cooked food that even the pickiest of the picky eaters loved. I’d get to meet the rest of my cabin at dinner. I’d start to settle in.

* * *

“So,” I said, thirty minutes later, sitting around a table with the rest of my cabin, plus Lyla and Emma, our junior counselor, “what’s everyone named?”

We went around.

“Emily.”

“Nora.”

“Lily.”

“Meghan.”

Suddenly, a girl opened the door to the dining hall, looked around, smirked, and came over to our table. “I’m Mia,” she said. She didn’t just say it. She said it in a way that lets you know who’s boss. I shrunk back a little. Paranoid, I know—but better safe than sorry. I decided I’d keep my profile low around Mia.

“Oh,” said Lyla. “Hi, Mia. Have a seat.”

She stood for a minute, staring at us like there was something obvious that we were forgetting to do.

“Move,” she finally said to me. Not wishing to make an enemy on the first day of camp, I obliged.

“Nice… hair,” I told her, trying to make peace. It was. It was long and golden and highlighted pinkish-red. “The highlights are nice.”

Mia scoffed and didn’t say anything. Not a good sign.

* * *

The rest of the week went on. I rode a boat, made some nice friends, drew outside or in the art shed, and tried to tell myself that everything was going great.

But it wasn’t.

Whenever I walked into the cabin, be it bed, changing into a bathing suit for free swim, getting ready for dinner, or fetching something that I’d forgotten in my trunk, Mia was there, ready to tease us, laugh at us, make mean remarks about us, annoy us, or tell us off. And she never ran out of ways to hurt people’s feelings. Never.

“Write about what a great time you’re having!” my dad had said as we kissed each other goodbye. So I did. I wrote home every night about activities, about my newfound friends, Nora and Meghan, and the delicious dinners that Margot, the camp’s cook, had most recently prepared. I didn’t write anything about Mia.

* * *

One morning, as we were getting ready for breakfast, we were all sort of acting silly, playing around. Nora jumped on Mia’s bed. “Whee!” she shrieked.

Mia laughed, too. That was one of the few times I’ve ever heard Mia laugh.

Nora did it again, three times over. Everyone giggled.

“Stop it,” said Mia. “Move. I have to put on my clothes.”

Nora got off but kept giggling. She made a puppy face at Mia. “Just a little bounce?” she asked.

Mia’s face turned stony. We all knew this wasn’t a good sign. “Nor-” I said, trying to warn her.

“One more little, bitsy time?” Nora pleaded. “One more? Just one more?”

“No!” Mia yelled. Then her face hardened into an evil kind of grin. “Nora,” Mia said, “I don’t like you anymore.”

I don’t like you anymore? Really? Could she have said anything less mature, less thoughtful? Thoughtful. Thoughtful is the opposite of what we’re thinking about here. Thoughtful is the opposite of Mia.

I found Nora on the bed that day, crying and crying into her pillow. “Hey,” I said, “what’s up?” I knew I didn’t have to. I knew perfectly well what was up.

“M-Mia,” she said between sniffles. “Sh-she d-doesn’t like me anymore.”

I reached over and sort of patted her. “Don’t pay attention to Mia,” I said. “She’s a jerk to me too. She’s a jerk to everybody.”

“Last year,” Nora sniffled, “last year we were best friends at camp. I d-don’t know what happened.”

“You’ll be fine,” I repeated. I knew I sounded dumb, like something cheesy out of a movie, but I didn’t know what else to say. We sat there, together, for a little while. Then the dinner bell rang and we ran to the dining hall. Tonight it was spaghetti.

* * *

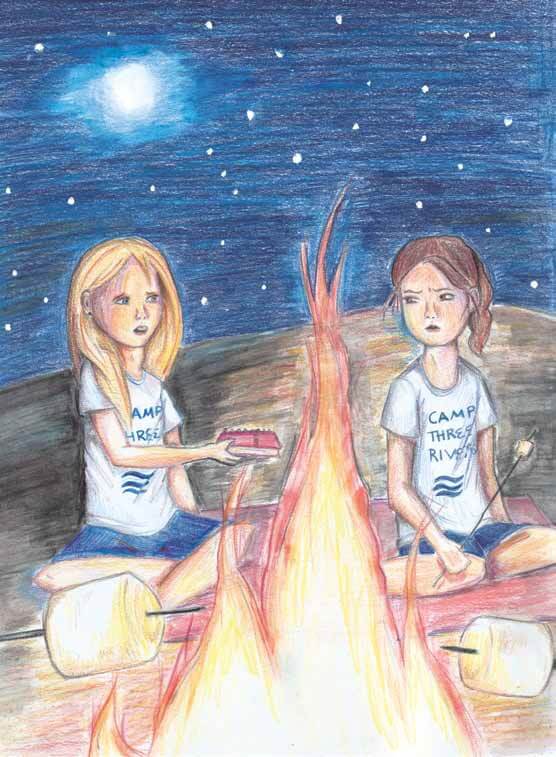

A couple days later, something strange beyond belief happened. I love to write poetry, and I had been reading one aloud every night at the campfire. Mia had never really congratulated me or anything, but one night, out on the beach, she shyly—is it possible that Mia could do anything shyly??—approached me.

She sat down on my towel and pulled out a pink notebook. “I… I’ve been writing a little…” she said, “and I was wondering… if you could read it?”

She sounded sweet. She sounded… nice! Like… a little kitten, or something! What was wrong? Was she sick? Was she being sarcastic? She didn’t sound it.

I nodded. “Y-yeah,” I said. “Sure I’ll read it. I’d be glad to.”

Mia tore a page out of her notebook but hesitated a little before she gave it to me. She looked like she was about to say something. Finally, she took a breath and spoke, so quietly that I could barely hear. “I… I’m… I didn’t… I’m s-”

Nora walked over and saw us talking. She frowned. “What’s up?”

Mia’s voice went back to the harsh tone that we were all used to. “Leave us alone!” She took a deep, shaky breath and pursed her lips together.

Then she passed over the crumpled slip of paper that she’d ripped out of her notebook a few minutes ago, on which was written the best poem I’ve ever read. I don’t even remember what it was about—just how good it was, and the strange sensation that this was something that you would read about happening in a book. Or maybe it wasn’t the poem that was so amazing. Maybe it was the fact that Mia—aloof, bitter, resentful Mia—had almost switched over to her other side. I hadn’t known she even had another side. From now on, I wouldn’t think of Mia as the bully who sort of ruined my camp experience. I’d think of her as the erratic bully who wrote poetry. Poetry!

“It’s really good,” I told her, my voice a little shaky. Not shaky because I was scared—shaky because I was, I don’t know, so surprised. Touched, I guess, would be the word.

She sort of raised her eyebrows. “Thanks, I guess.”

We sat there for a few minutes, silent. Then Mia walked away.

* * *

I could make this the end of the story. I could pretend that after this, everybody had a realization that Mia was, underneath, the nicest person, the best poet, and forgave her. But that would be a movie ending. It would be cheesy. And second of all, that wasn’t the end. The day after, Mia called Meghan stupid and told Nora twice that she looked dorky.

I went home three days later. Back to my family. Back to my apartment, my bedroom. Back to my friends. Away from Mia. I might never see her again. I most likely won’t. But whenever I think of camp, I’ll remember Mia, Mia’s bullying, Mia’s poem…