Madeline anxiously gathered her books and half-jogged towards the classroom door, praying that her Civics teacher, Miss Jones, wouldn’t notice her. “Madeline, can I speak with you for a moment?” Madeline’s Civics teacher called in her high, soprano voice. Her eyes scanned the room and then narrowed when they met Madeline’s. Madeline heaved a sigh. So much for being unnoticed. I bet she’s going to call your parents, Madeline silently thought, scolding herself. She made her way to Miss Jones’s desk, prepared for the worst. Miss Jones towered over Madeline and pointed a perfectly manicured finger at her. “I told you last week that you need five community service hours to pass my class. Why don’t I have them?” Miss Jones snapped. “I’m sorry. I guess I forgot. Besides, I have drama and acting classes filling up my time,” Madeline mumbled apologetically. Miss Jones huffed. “Because of your procrastination, I have no choice but to assign you a project.” She rummaged through her desk drawer, searching for something. Madeline groaned. She’d heard rumors about the handpicked projects from Miss Jones. Two kids received trash duty and one even got a job volunteering at the local jail. Madeline imagined herself picking up a rotten banana peel on the side of the road or talking to a prisoner with face piercings and shuddered. Miss Jones finally pulled out a flyer and placed it in front of Madeline. “That’s really cool. Can you tell me about it?” Madeline asked, amazed “This is an advertisement from Nature’s Nursing Home. They are looking for volunteers to help entertain the elderly there. The number and address is at the bottom,” Miss Jones said smugly. “I have to babysit old people?” Madeline screeched. “I don’t have time! There’s a reason why their friends and family don’t visit them anymore. This will be so humiliating.” Miss Jones frowned in disapproval. “You will start next Monday, volunteering right after school. Don’t skip this,” Miss Jones said, shoving the flyer in Madeline’s hand. That night, Madeline tried to forget about Miss Jones’s idea during dinner, but it was nearly impossible. She pushed a piece of chicken around her plate and dug holes in her rice. “Are you OK, Madeline?” Madeline’s mother asked and then shot a look at Courtney, Madeline’s older sister, who was playing on her phone. “Yeah, I’m fine,” Madeline replied, looking down at her plate. “You actually look kind of horrible. Did your friend realize that you’re a doofus? Oops, you don’t have any friends,” Courtney snickered. Madeline stuck out her tongue. She wasn’t in the mood for her sister’s juvenile comebacks. “Courtney!” Madeline’s mother exclaimed. Later, Madeline decided to do her homework. She dumped the contents of her backpack on her bed and searched for her math worksheet. When she was searching on her bed, Madeline’s eyes traveled to the half-crumpled Nature’s Nursing Home flyer that she shoved in her bag that afternoon. Madeline sighed, grabbed the flyer, and went downstairs to the kitchen phone. * * * When Madeline walked inside Nature’s Nursing Home on Monday, her instinct was to run away and accept a failing grade from Miss Jones. Instead, she kept her head down as she made her way to the front desk. “Hi, my name is Madeline. I’m here to volunteer to entertain the old, sorry, elderly people here,” Madeline said politely to the lady at the front desk. The lady smiled. “That’s excellent. We don’t get a lot of volunteers, never mind young ones. Many people are hostile toward the seniors here. Follow me, please.” The lady led Madeline to a door and knocked twice. It was very quiet until a frail voice answered, “Come in.” Inside, the room smelled heavily of perfume and baby powder. A bed lay towards a corner, unmade, and an assortment of cards and game chips were scattered all over the bedroom floor. Sitting on a chair next to a square table sat an old woman with frizzy, gray curls forming a halo around her head. Her floral shirt and blue jeans stood out against her pale skin. “This is Mrs. Blair, the senior citizen who you will be spending time with every day this week,” the lady at the front desk said proudly. She gave Madeline a wink and shut the door behind her. Madeline stood awkwardly in front of Mrs. Blair. She cleared her throat and spoke. “Hello. I’m Madeline.” “Hello, Madeline. You have a pretty name,” Mrs. Blair replied. “Thank you,” Madeline replied shyly. “May I sit?” She gestured to the other chair. “Sure,” Mrs. Blair shrugged. Silence filled the space between them. Mrs. Blair’s eyes shifted to and from Madeline to the room. “Tell me about yourself, Madeline,” Mrs. Blair said suddenly. “Well,” Madeline started, “I don’t have any grandpas or grandmas, so I can’t relate to elderly people much. I love the performing arts. I’m mainly here because I have to volunteer here to get a good grade in Civics.” As soon as Madeline said the last sentence, she winced. Mrs. Blair didn’t seem to mind. “Many people, especially teens, don’t seem to care about old folks like me. Thankfully, I’m going to change that about you. Ask me anything.” Madeline thought for a moment. “What was your job?” Madeline finally decided. “I was a Broadway star in New York,” Mrs. Blair answered, looking down. “That’s really cool. Can you tell me about it?” Madeline asked, amazed. Mrs. Blair grinned. “It was in 1948 and I was fourteen at the time. There was a crazy superstition that the lead actor or actress had to wear a special bracelet or they would be cursed forever in their acting career. Back then, I was the lead in almost all of the plays so I always wore the bracelet. Till this day, I still have it and used to wear it when performing plays for the others here when I was more flexible.” Madeline laughed along with Mrs. Blair and listened carefully to

Don’t Talk to Strangers

A TRUE STORY “Yeah, I think just a cheeseburger will be fine,” I told my dad as we stood outside McDonald’s. “I’ll take Beacon while you do that.” I grabbed my dog’s leash from my father as he strolled into the restaurant. Seconds later, my brother emerged. We watched as cars, spewing smelly exhaust, drove past. A navy-blue Mercedes suddenly stopped, leaving a car sitting irritatedly at the drive-through window. The window opened and a man with a face the shape of a perfect oval and hair that was graying and balding appeared. He said something that was inaudible over the rumble of his car and then repeated it. I swear, I had never seen the guy before. He was a total stranger and I probably will never see him again. “What breed of dog is that?” the man asked. “’Cause I had a dog that looked just like him.” “He’s a Maltipoo,” Atticus replied. I was lost for words but I managed to utter, “A Maltese-Poodle.” All there was in the world were the dog in the picture, Beacon, and me The stranger pulled out a brown wallet. He opened it up and I saw what I thought was a picture of the Beakmeister himself (the Beakmeister was my father’s favorite nickname for Beacon). The dog in the picture had Beacon’s silky fur and black nose and pinkish tongue. The dog curled his tail up against his back like Beacon did when he was happy, and most dogs didn’t. He had Beacon’s floppy ears too. I wondered if the two dogs were related. “This is him,” said the man. I jumped a little. I had almost forgotten he was there. All there was in the world were the dog in the picture, Beacon, and me. I saw a little bit of something in the man’s eyes go out, as if in longing for the dog. He tightened his lips a little and dropped the wallet abruptly. Reluctantly, he tore his eyes back to the wheel. “Take good care of him,” the man murmured, and drove off. I scooped up Beacon and hugged him close. Annabel M. Smith, 11Manchester, Massachusetts Elena Delzer, 12Suamico, Wisconsin

Scarlet Spring

Kanuna stood silently in the soft, grassy meadow, taking in deep gulps of the fresh spring air. The winter had been timeless and bitter, but now spring was here. It was only a few weeks ago when Kanuna had noticed the first little shoot of grass shyly peek its head through the silent blanket of snow. Now, there was not a single patch of ice or snow left. The rivers were teeming with snowmelt, and the meadows were as vibrant as ever. He felt as if the spring were the best thing that could happen to him right now. Kanuna strode over to the river. He could just barely make out the form of his mother, standing at the edge of their village. “Kanuna!” his mother called. “Kanuna, is that you?” “Yes!” he shouted over the roaring river. “Get over here,” his mother scolded. Kanuna deftly got into the canoe, picked up the paddle, and crossed the river. “Go to your father. Don’t you remember—he’s teaching you how to hunt today,” Kanuna’s mother scolded. How could he have forgotten? Kanuna slapped himself in the forehead. He’d been looking forward to this for a while. “Hello, son,” called his father. There are many benefits to having a father who is the chief of a tribe. Today, he was going to learn how to hunt. “Follow me!” he called. They walked for half an hour until his father suddenly halted. “Be careful and quiet,” he whispered toward Kanuna, who was still ten feet behind him. There was a deer in the meadow. Kanuna shivered with excitement. He drew his bow and, under his father’s instruction, aimed for the eye and fired. The arrow went straight and clean, into the eye. It would have been a quick and painless death for the deer. They carefully made their way out. They were halfway across the clearing when the gunshots went off. Wild with fear, Kanuna looked to his father for help. The last thing he saw was a hoof hitting him in the forehead “Ru-” his father was cut off as a terrible gurgling noise issued from his mouth. Kanuna looked at the chief’s chest and saw a bright red dot spreading itself slowly but persistently across his shirt. Kanuna started sprinting across the meadow. He was at the treeline when he was cut off by a horse rearing up in front of him. The last thing he saw was a hoof hitting him in the forehead before he blacked out. * * * Charles woke up with his head buried in the pillow. He sat up, coughing in the acrid fumes of burning firewood, his father’s cologne, the stink from a dead bird on the roof that was far along in the rotting process, and his own sweat. “Charles!” his father shouted up the stairs. “Are you up yet?” He gagged in response. “Well get a move on!” his father said. “Don’t you remember? You’re coming with us today to secure more territory!” Charles had been waiting for this day his whole life. There were benefits of having a father who was the warden. He and his father had come on a ship to the thirteen colonies, just like the rest of the town. But having no second-incommand, when the mayor was killed by the natives, the responsibility of leadership fell on him. Charles’s father was the warden of the town prison, and he burned with a hatred for the Native Americans. His sole goal was to conquer land for farming. People still called him Warden, although he should not have been called that anymore. “On my way!” Charles called. A half hour later he, his father, and ten or so other settlers were seated on their horses. “Follow me!” called his father to the band of settlers. “Be cautious! The natives are extremely hostile.” Charles wondered why the natives were opposing them. They were just taking what was rightfully theirs, after all. Half an hour later, they came to a clearing. Everyone spread out in a half circle around it. There were no natives; the settlers’ attention was on a deer. They were licking their lips and loading their muskets when an arrow soared out through the clearing, hitting the deer straight in the eye. The warden quickly held a finger to his lips, silencing the others. A grown man and his son, both natives, crept out into the clearing. “Fire!” the warden shouted. A musket went off and the man dropped to the ground. The child ran across the meadow towards the trees. One of the settlers cut him off and, while it was rearing, his horse’s hoof knocked against the child’s forehead, a bruise already blossoming yellow, purple, and black. He slumped to the ground, unconscious. Charles’s father commanded the settlers to move forward and he tied the child up and slung him over the saddle. Charles looked from the bruised child to his father, lying now in a pool of blood. Numbly, he thought, This is why they’re hostile. In fact, we’re the hostile ones, and they’re just defending themselves. The rest of the ride home was quiet, but there was an air of victory among all but Charles. The group dispersed, and he was left alone with his father and the unconscious form now slumped on the ground. “What did you think?” the warden asked. Charles just nodded. Honestly, this had been the worst day of his life, but he wasn’t about to tell his father that. “Go put this child in the cellar and lock the door, there’s a good boy,” ordered his father. Charles tromped down the stairs, his and the boy’s weight combined making the pine boards creak. The cellar was a damp and moldy room, with brick walls, a stone floor, and one small window with iron bars on it. Just as Charles was closing the heavy oak door, he saw motion behind it. “I know you can’t understand me,” he whispered, “but

High Dive

My toes curl and uncurl on the sandpaper-rough diving board. I shiver as I stare into the glittering pool. The chlorine smell turns my stomach. I know I’m eventually going to have to jump, but I just can’t. I stand, letting the wind chill my tan skin. It’s the last day of summer, and I’m determined to conquer the high dive. I hear another groan escape from behind me. I glance back. Marcy, my best friend, impatiently taps her pink nails along the metal ladder. “Hurry,” she mouths at me. Another mosquito nips my arm, and I slap it away. I try to ignore the incoherent whispers down below. This time I’m going to do it. I bend my legs, flex my muscles, and do a little hop. The whole board quakes, and I let out a little scream before grabbing the railing. I hear Marcy’s snort over the racing of my heart. I grip the railing with my shaking hands. Just don’t look down. Just don’t look down. I stare at the deep blue sky patched with pink. “She’s never going to do it,” I hear Amy Andrews grumble from below. Dark strands of hair flutter in front of my face, escaping my thick ponytail. That’s when I know I can’t do it. I begin to make my way towards the ladder with wobbly steps before disappointment and embarrassment can overwhelm me. Don’t let them see you cry. “I’m Lisa,” she says, cheerfully. “It really sucks that you got pushed.” “Jeez,” Marcy says, stepping onto the diving board. She strides towards me, forcing me to take about seven steps back. “What are you doing?” I squeak. She takes a few steps toward me and pushes, hard. I scream, falling and falling towards the water. My arms and legs flail uncontrollably. I hit the water with an icy slap. My skin stings as bubbles tickle their way up my body. I hang there a moment, suspended under water. My heart screams in my head. I can’t think anything. Finally, I kick hard and break the surface. I stare up at Marcy. She looks like a queen on top of the diving board. “Why did you do that?!” I shout, sputtering. She rolls her eyes. “Oh, relax. You finally jumped off the diving board. Aren’t you happy?” she says, glancing nervously back at the people in line. Most of them didn’t even pay attention, but I know she hates it when someone makes a scene. “You pushed me,” I accuse lamely. “I was only helping,” Marcy says, rolling her eyes again. “Now you might want to move, or else I might crush you.” I force smooth strokes to the edge of the pool. Acid tears fall into the water. I hear Marcy’s happy squeal and splash. I climb out stiffly, wrapping a fresh towel around my waist and slinging my new swim bag over my shoulder. “Excuse me,” says a voice behind me. I quickly wipe away tears. I turn and stare at a girl with sunkissed skin in a red bathing suit. She smiles at me, and her smile feels like a refreshing spray. “I’m Lisa,” she says, cheerfully. “It really sucks that you got pushed.” I adjust my bag strap and look at my feet. I feel the tears about to well up in my eyes again. How could Marcy do that? “Do you want to sit with me?” she asks. What I really want is to go home and lie down in the clean sheets and forget about today. “Sure,” I say, smiling as kindly as I can. “I’m Mia.” She sucks in a breath of air and then gives me a small smile. “Follow me,” she says, before leading me off. Together, we brush past the dry hedges and go behind the locker rooms. You get a perfect view of the high dive. Queen Marcy is right back up there. We reach a fountain, and I can’t help but notice the sunset reflecting on its calming surface. It’s filled with pleasant round pebbles that remind me of sea glass. It’s a special place. I take a seat at its base and face the hedges. How I wish I could ignore the kids jumping off the diving board with ease. I stare longingly at them. Why is it so easy for them? I wonder. I imagine how weird I must’ve looked falling, flailing, and screaming from the diving board. I want to cry all over again, but I just sigh. Lisa lies next to me, her curly hair stretching across the cold cement. Unlike me, she’s staring up at the sky, her eyes butter-soft. My muscles begin to unclench, and I listen to the trickling water. I turn to her and say, “I want to be able to jump off the high dive just like everybody else.” Lisa turns and stares at me. I push a soggy strand of hair behind my ear. “I know. You’ll do it someday” she says, giving me that ocean-spray smile. “Have you ever felt that way?” I ask. “I mean… about anything?” Even though I’m being very awkward, she just closes her eyes and sighs. “I moved here at the beginning of summer. My mom wanted me to go to this pool, so I came. I watched everyone buy frozen lemonades together and take selfies. I was always alone, sitting in my chair, with a melting lemonade and a camera with no memories. I never had the courage to ask somebody to hang out with me, but then, I finally did.” Her eyes sparkle as she turns to me. “I found this place a few weeks ago. I call it The Golden Fountain. It looks like it’s come straight out of a fairy tale, right?” “Yeah, it does,” I smile. I’m done with Marcy but I’m not done with that diving board. I will conquer it. We watch the sun sink and stars slowly sprinkle across the sky. Lisa tells me

The Songs of Green Waters

We call you, songs of life serene, You dive, our beauty never seen Until you’re trapped in worlds of green. To land you won’t return. For beauty won’t your life you trade And join us in a brief parade? The countless lives we’ve took and played All men for beauty yearn. So join us, hear our siren song Your lifetime left you’ll come along Until no more for breath you long So turn, green waters, turn. O gentle waters turn. – Ariella Pearl There was a conversation going on at the moment, but I wasn’t paying any attention to it. I added in a “cool” once in a while, but my mind was far away from my cousins’ small talk. I stood, clad in a damp T-shirt and swim trunks, on the wet sand of the beach, the ends of waves lapping at my bare feet. My two cousins, Kyle and Mark, stood by me in similar beach garb, involved in a conversation that included various and frequent interjections of “dude,” “man,” and “bro.” For Mark and Kyle, this was the height of the Californian beach experience: looking cool, wearing overpriced sunglasses, and exclaiming over bikini-clad, blond-haired, sun-tanning teen girls. I was uncomfortably bored with their so far fifteen-minute-long conversation about a certain exceptionally “hot” bikini-wearer. I wanted to be deep out under the ocean, my new goggles strapped over my face, with a clear view of the green, underwater world. But Mark and Kyle would have none of that, especially the goggles, which they said made me look like a dorky robot. I noticed that her eyes were almost exactly the shade of the ocean “Jarren!” I broke my gaze from the ocean horizon at the sound of my name. “What?” I turned to Kyle, trying to pretend that I had been interested in what he was saying. Kyle groaned. “I said, ‘Jarren, check out that…’” But, even though it was no doubt some girl, I never got a chance to hear exactly what I should check out. A skinny, pale-skinned girl on a boogie board, with dark, stringy hair and a seagreen one-piece bathing suit, was ejected from the ocean with the waves, whooping and cheering as she shot right into Kyle, knocking his legs out from under him. “Oh!” The girl jumped to her bare feet and flung her dark, stringy hair over her shoulder, revealing a face clouded with freckles. “I’m so sorry!” She took Kyle’s hand and yanked him to his feet with a surprising amount of strength in her skinny arm. “Are you OK?” She peered into my cousin’s face. “There’s no way to steer on these things, you know. Someone should invent boogie boards that steer, don’t you think?” Her voice came out in a lively, enthusiastic burst that made me wonder whether she took the time to inhale at all. “No problem,” Kyle said quickly and shakily, stealing a glance at Mark. All three of us turned away from the girl, expecting her to rush sheepishly back into the ocean. Kyle and Mark returned to their conversation and I, imagining the quiet peace I could have beneath the ocean, looked towards the sea— and found myself faceto- face with a freckled, dark-haired girl: the kid with the boogie board had never left. “Oh!” I took a leap back. “Er… um… are you OK…?” Oddly, to my surprise, I noticed that her eyes were almost exactly the shade of the ocean. “Yeah,” she said perkily, looking unfazed. “My name’s Rosie.” She stuck her hand towards me. “Um…” I looked over to Kyle and Mark for help, but they’d abandoned me and moved on to another conversation on their own. The girl, Rosie, reached down and grabbed my hand, giving it a firm shake. “I- I’m Jarren…” I stuttered, not wanting to hurt the kid’s feelings but longing to leave the awkward situation. “Nice to meet you, Jarren.” Rosie kept her grip tight on my hand. “Come on, you aren’t really interested in what those guys are saying anyway. Why don’t you come and swim with me?” She gave my hand a hard tug. “Listen, kid, I can’t…” “Who’re you calling kid?” With her freckled face screwed up in anger, she could have been a laughable sight, but I, a head taller than her and much heavier, was strangely frightened. “I’m thirteen years old,” she said proudly. “How old are you, anyway?” My face flushed, an annoying attribute that popped up at the most embarrassing times. “Th-thirteen,” I stammered. Rosie humphed triumphantly. It was hard to believe this scrawny little imp was my age; she was a full head shorter than me and looked unhealthily skinny, like someone who had been starved or underfed. Her swimsuit hung as loosely on her tiny frame as someone’s baggy jeans might. “Just come on, OK?” she said to me, never loosening her grip on my hand. “We don’t have to go swimming. Don’t you like books? I’ll show you a really great book.” I completely froze in my tracks with enough force to make Rosie’s fingers untangle themselves from mine. Suddenly, I was shaken deeply. I did like books, but how did she know? How did she know that I would have rather been enclosed in a solitary garden or forest, living incredible adventures through written words, than here, looking cool on the beach? She could have been a good judge of character who randomly popped out of the ocean. Or, she could have been something more than that, something abnormal, something fantastical like you’d find in a story… “Jarren?” Rosie turned toward me. I hesitated a moment. “Yeah… yeah, coming.” Then, somehow finding my hand back in Rosie’s, I followed the tiny sprite of a girl beyond the sands of the beach. * * * Why do I need to see this book so badly, anyway?” I was squatting in a sparsely furnished room, wondering why I ever followed this little stranger to her

Rainbows in the Sun

I never knew how small the fountain could look Water trickled from in between the cracks of the fountain, the sun glinting off its surface as it set, going drip… drip… drip… I watched the water splatter into my palm. I never knew how small the fountain could look. I used to be smaller than a soda can, with wings and bright blue feathers. I used to drink from this. I used to fly about the lakes, flip about the treetops and see rainbows in the sun. I wouldn’t think of eating anything other than birdseed. I never saw the world as the big, fast, killing predator. Just the innocent prey. But then… the bullet… a flash of light… then darkness… and I was back. Just… not as a little blue jay. I had become akin to the one who killed me, ate poultry and fish and hamburgers and cheese sandwiches… But normal people don’t remember being killed… or their lives before. They only remember their current life. I stared at the water in the fountain… I could not see the rainbows in the sun. Only the darkening sky. I can’t see anymore. And… a warm glow spread across the water as the moon hit it. I can see again. The woods loom large around me, their shadow and mystery curling around me, holding me close, hugging me tight. I hear my former predators, the night owls, hooting and flapping their wings like I wish I could. I hear the rustling of leaves, feel the light of the moon on my face, and the ground beneath my feet. Maybe tomorrow, I will also feel the wind beneath my wings. Hannah Mayerfield, 10Scarsdale, New York Matthew Lei, 11Portland, Oregon

Growing Season

“Ryan, honey, guess what?” Mom bounced into the room, a cheerful smile on her face. “Grandpa just called. He is delighted to have some extra help on the farm this summer!” Oh no! Ryan thought, dragging his eyes away from his tablet. He pulled off his headphones. “But, Mom! We’re going to Disneyland this year!” Mom’s brow wrinkled. “Oh, honey, we can’t quite afford Disneyland this year. I’m sorry. I know you want to go. But Grandpa needs your help, and besides, a real-life experience is far more precious than Disneyland could ever be.” Her smile was back. Ryan groaned and went back to his game. Maybe this was all just a crazy dream. But it wasn’t. Two weeks later he found himself hugging Mom goodbye and boarding a plane for middle-of-nowhere Montana. Grandpa picked him up at the tiny airport in a beat-up white pickup, hardly visible under layers of dust. “Hi, Ryan,” Grandpa greeted him. “Hi, Grandpa.” Suddenly, a furry mass catapulted out of the car and tackled Ryan, covering him with kisses. Grandpa chuckled. “That’s Bolt. I think she likes you already.” Understatement of the century, Ryan thought as he heaved the dog off of him. Grandpa lifted first Ryan, then his suitcase into the truck. “So, you excited to work on a farm?” “It ain’t much, but it’s home!” Ryan didn’t bother to remove his headphones. “No,” he mumbled under his breath. After a good hour of driving along mostly unpaved roads, the pair reached Grandpa’s small farm. There was a little house surrounded by pine and cottonwood trees. To the left of that was the animal barn where the goat, Sukie, and the ten chickens lived. Behind the house was a blooming garden where Grandpa grew his vegetables. It sure didn’t look like much. Ryan scanned the roof, searching for a satellite dish—nothing. This house didn’t even have TV. Ryan slowly climbed out of the truck. Grandpa whistled as they walked to the front door. He flung the door open wide. “It ain’t much, but it’s home! Ryan, your room is upstairs. Can you find it OK?” “I guess.” Ryan could hardly remember his last visit here, but the stairs were right next to the front door. He trudged up them, opening the first door he found. It was a tiny, plain bedroom. Ryan deposited his suitcase on the floor and surveyed his surroundings. In the corner of the room was a large window. He glanced out. A lush, emerald field stretched to the edges of the boundless sky. On the very edge of the horizon, a faint blue smudge of mountains was visible. Bored, Ryan shifted away from the window and flopped on the bed. He switched on his tablet, tapped his favorite game, and waited for it to load. The moment was ruined, however, by Grandpa’s call up the stairs. “Ryan, you settled in? C’mon down, we got some work to do.” Grumbling, he thumped downstairs, trailing headphones. “There you are.” Spotting Ryan’s tablet, Grandpa held out a hand, face creased with an odd expression. “Why don’t I keep that safe for you? I don’t hold much with these newfangled electronics. Besides, we’ll be so busy this summer you won’t have any time for it.” Ryan’s mouth fell open a little and he stared at the outstretched hand. “But, Grandpa!” “No ‘buts’ about it.” Grandpa’s eyes twinkled. A shocked Ryan slowly handed over his prized possession. First I had to come to this stupid farm to work all summer. Now this! It was inhumane. “All right. First thing, we got to change the irrigation.” So Ryan, clad in tall rubber boots and armed with a shovel, walked out into the field with Grandpa. Bolt trotted happily along, and while the two shoveled mud and changed the canvas dam’s position to redirect the water flow, she hunted mice in the grass. Then Ryan fed the flock of chickens. They gathered around his feet in a fog of feathers. After that Grandpa cooked supper and Ryan had to wash the dishes. He finally fell into bed, exhausted to the bone, or so he told himself. When Ryan opened his eyes, Grandpa was shaking him. “Wake up, son! Time to milk!” It took Ryan a moment to register his surroundings. And then he groaned what he imagined to be a groan of long suffering. Really, he just sounded pathetic. “Get dressed and meet me at the barn.” Grandpa clomped down the stairs but Bolt jumped on Ryan, refusing to let him fall back to sleep. She wagged her tail fiercely and gave an exuberant bark as he pulled himself out of bed. He yawned and glanced at the clock. What is this unimaginable hour? Good grief! No one should be forced to rise before the birds!!! But he yanked on his clothes and wandered out to the barn. Grandpa was in the barn, sitting on the milking stanchion (a sort of table) with Sukie on top. There were two slats which held the goat’s head in place and a box for her to eat out of. Milk was streaming from her teats into a bucket with clear regularity. Grandpa glanced up from his work and saw Ryan, who was standing uncertainly in the corner. “You come try,” he commanded. “Hold the teat like this, pinch it off, and squeeze the milk down.” He guided Ryan’s hands through the motions. Ryan was clumsy. By accident, he squirted his shirt with milk and the sticky warm felt queer against his skin. After the milk was strained and put away, the irrigation had to be changed again. So Grandpa moved the canvas dam and Ryan shoveled the wet dirt into mounds, while Bolt hunted. When they finally got to eat some bacon, eggs, and toast, Ryan’s thoughts kept straying to his tablet and all the great games and things he was missing out on. Maybe, just maybe, he could convince Grandpa to let him have it back again.

My Hammock

Still. Suddenly, a sweet song, a lullaby. Swinging now. A hush a shush a soft touch caressing my sharp elbows, my shivering toes, my rounded cheeks. Swinging now, Swathed in silken material hush, hush, hush Goodnight sun alone but content not lonely several long seconds… Swinging now. Stars smile at me sprinkling light Each star, its own star like snowflakes. Individuals. Swinging now. I sleep dreams tiptoeing across my mind slippered feet sliding silently. I sleep Safe in my hammock. Swinging now Anamaria Grieco, 13Brookline, Massachusetts

Tracks

I go to the tracks to think, The ties go on for miles. They let me see the world, They remind me how small I am. The bushes creep into the dirt in the cracks, Even in synthetic structures there is nature. They have sat here long enough to be ruins, And trellises for invasive vines. But they were once signs of progress, Human civilization creeping over unclaimed lands. I go to the tracks to think, There’s a rock a few yards off. It’s big enough to sit on, So I sit and watch. Most remnants of the tracks’ glory days are gone, But I can feel the rush of the wind as the trains hurtle past. Ellanora Lerner, 13New London, Connecticut

Topanga Canyon

Two white cars pass each other on the highway, One maneuvers easily around a red barn, through a twist in the highway, and towards the seashore’s fogbanks, Pulling up the canyon side, the other passes under the shady brambles of a glen, And its destination, far from sight, twinkles reflected only in its seeker’s eye. Now the first car is only a speck on the horizon; the ocean is far from me but not from it, Going fast, the second car enters the woods’ splintered sunlight, unseen to my eye, gone like the nighttime stars, And as the morning star fades, I recall how soon I will have to get in my car and leave this paradise. Coyotes, far on the other side of the canyon, howl; can they feel the loneliness in the air, too? A finch hops onto an ancient locust tree’s limb, its feathers creating a halo of sunlight and joy, Not a care in the world, the finch lifts off, its sequined shard of light following it wherever it goes, Yammering, higher on the cliff; our neighbors’ chickens awake to the already bright sky. On the cliff, I sit; I can see the Pacific before me, like a mirage, moving away through my car window… Now my dream vanishes: I am still here, still sitting in this wondrous place, but for how long, I cannot say. Edie Patterson, 10Lawrence, Kansas

Blackbird Fly

Blackbird Fly, by Erin Entrada Kelly; Greenwillow Press: New York, 2015; $16.99 Have you ever longed and hoped for something you never had? Like blue eyes, or soft yellow hair? Those are the things Apple Yengko longs for night and day. To not come from a different country. To not have a mother who does things differently than other mothers. To be the same as everyone else. Have you ever felt this way? Then you should read Blackbird Fly. Apple Yengko is from the Philippines. She was born there, and that was where her father died. Her mother couldn’t stand to still live in the same place. Too many memories. So they moved to America. Apple is conscious of her looks and how her mother talks. She goes to Chapel Hill Middle School in Louisiana. The kids make fun of her because she looks different. Looking different can either work for you or against you. In her case it works against her. They even put her on a list that marks her ugly. But then a bad mistake is made that somehow helps Apple make new friends and learn that being different from everyone else isn’t so bad. One main theme of Blackbird Fly is that being different isn’t a bad thing. Sometimes it’s a gift. It’s OK not to blend in with the crowd. You don’t have to always be the same as everyone else. The author made the passion of the characters so strong. Feelings jumped off every page! It was also a little funny at times. You would immediately feel trust, sympathy, and compassion for Apple. Apple’s mother is always raging about American ways and choices and friends. It makes Apple wonder, if her mom is always talking about how much nicer or more friendly or healthy the Philippines are, why did she move her to America? This book is a cliffhanger and will deeply impact your emotions. The best thing about this book is that you can really relate to the main character. One terrible thing that happens in this book is that Apple’s friends don’t turn out to be so friendly and are really harsh. They backstab her when she least expects it. One time a really good friend of mine backstabbed me and I was hurt. But I got through it, and so did Apple. The things that happen in this book seem so real and you can totally relate to Apple’s good moments, seriously embarrassing moments, and terrible and confusing moments. It makes the book seem so real because things like that happen all the time. All in all, this was a five-star book for me. It made me gasp, sigh in relief, and shudder all the while I was reading it. This book was very satisfying, but also completely and truly shocking in some ways. Blackbird Fly is a fantastic read! Ramsey E. Stephenson, 11Washington, DC

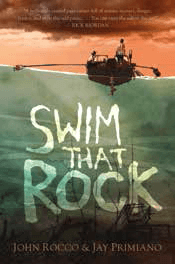

Swim That Rock

Swim That Rock, by John Rocco and Jay Primiano; Candlewick Press: Somerville, Massachusetts, 2014; $16.99 If you want a book with daring adventures and even pirates (gasp), then Swim That Rock, by John Rocco and Jay Primiano, would be the perfect book for you to cozy up on the couch with. The book zooms in on Jake Cole, whose life is about to change drastically. After his father’s disappearance/ assumed death, Jake walks out of his house with a motive— a knife with his father’s initials was left in his gate, and he must find the person who left it. He runs into this man, who gives him only the name Captain. Captain is wearing “rubber boots, worn jeans, and a red flannel shirt… (with) black hair… matted across his forehead.” He leads Jake on a semi-legal journey, which earns Jake 300 dollars. But this is just the beginning. Jake and his mother, along with their friends Gene, Tommy, and Darcy, must earn 10,000 dollars in one month or lose their restaurant and move to Arizona—which is most certainly not on Jake’s to-do list. Either by quahogging or by the Captain’s methods, Jake knows he must save his restaurant. One of the best parts of the book, in my opinion, is when Jake almost injures himself to save someone’s equipment—a person whom, chances are, he will never see again. When this guy, Paul, drops his brand-new equipment into the water, he immediately and dejectedly gives up. Seeing this, Jake jumps into the water to help Paul retrieve his equipment, almost killing himself after getting tangled in an anchor line. When Jake retrieves the equipment and gives it to Paul, Paul offers him money, which Jake refuses. Although it may seem kind of weird, as I am a thirteen-year-old, I have done the same thing. While shoveling my driveway, I watched my neighbor struggling to shovel her driveway across the road. I felt a pang of pity and went over to assist her. She pulled out her wallet, and I told her that I wouldn’t take it from her because people had shoveled my driveway for me, so I was just paying it forward. I cried while reading about Mary, the homeless woman. She had lived on the beach for seven years. Once she saw Jake on the beach she called home. She gave him a quarter and told him to call his mother. He originally said he couldn’t take her money, but she forced him to. He turned around to thank her, but she was gone. I couldn’t take it—it reminded me of the story in the Bible where the poor woman who gave a little but gave it all truly gave more than the people who gave a lot but had so much more. After reading this book, I couldn’t help but wonder if there are people throughout the world who are in hard situations like Jake. I know there are, and I hope everything works out for them—short term and long term. This book would be perfect for anyone from the ages of eleven to fifteen. I feel that anyone who hunts/fishes regularly would have an easier time understanding this book—still, though, it is good for anyone who likes strong protagonists who do not shrink in times of danger. Christian Rice, 13Quakertown, Pennsylvania