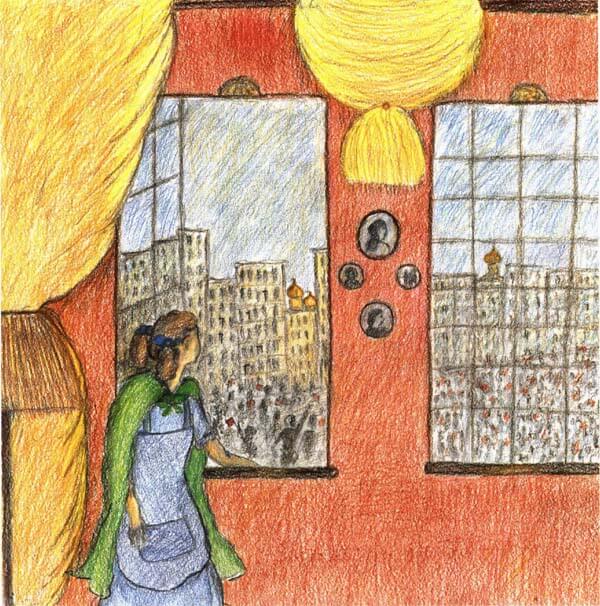

I started out the window, looking onto the surging crowds with sadness and fear. I had always known the revolution might happen—as if my brother, Anton, would ever let us forget. He was always out on the streets, socializing with the revolutionaries, showing me the small red flags he brought home. It seemed he enjoyed upsetting Mama—telling her that since we had a family of aristocrats, we may be targets for the revolutionaries. After we came to stay with Aunt Evelina for a while, he told us to always be ready to leave. Well, he had before they sent him off to the war. But revolutions were for France, not my beloved Russia. Oh, how far we had come from the carefree days when we skated down the frozen creek back at home. As I stuck my head out the window, I closed my eyes and listened to all the sounds around me. Suddenly, I heard a strange, muffled noise. I realized it was Mama standing out on her balcony, silent tears running down her face, continuing even when Papa came out and put his arm around her. I could hear their voices, even over the roar of the throng.

"Oh, Igor," Mama cried, "why can't the war just stop? Sometimes, I wonder what the tsar is really up to. Much as I love him, I cannot see how the war is doing any good for us. How could he send so many innocent men to their deaths? We all know that sending peasants with barely any training won't help us win the war. And it breaks the hearts of so many families. All I want is for the madness to end and for Anton to return."

At this, I gasped. Mama had never spoken out against the tsar! Things like that were for Anton and his university friends, back from before the war . . .

"Anitchka, hush, it will be all right," my father soothed. "You know that we were forced into this. Do not worry. The tsar will soon sort this all out. And you and Anya are working in the hospital, nursing the soldiers, are you not? I'm sure that soon, one of them will have news of Anton." But I could see his brow was creased, and I could hear the worry in his voice, a voice I knew well.

"I certainly hope so," Mama said tearfully. Papa began to say something, but I did not wish to hear more. When Papa was worried, things were not good. My strong Papa always knew how to solve our problems.

* * *

I longed to go back to our estate in the country. It wasn't as grand or nearly as big as Aunt Evelina's mansion here in Moscow, but it was wonderful. The workers were always good to us, because Papa gave them freedom and never let the supervisors beat them. Papa's methods were often looked upon with scorn by our neighbors, but he didn't care. And best of all, we were slightly isolated from the world, and we didn't have to hear so much terrible news. It took days for letters to get from the city to our house. I used to hate this part of our life—I barely ever got to hear from my friends in the city but now I realized how lucky we were. We had a simple lifestyle there. When we were little, Anton and I would explore the forest. I remember when we found the shell of a robin's egg. It was the lightest of blues, with a few faint cracks running through it . . .

All of a sudden, Mama came into the room and interrupted my thoughts. "Come, Anya, it is time for us to work in the hospital. Are you sure you want to go today?"

Mama asked me the same question every day. As if I didn't feel my best when I was working, helping the soldiers. I disliked sitting around doing embroidery like Aunt Evelina always encouraged me to do. "Ladies don't need to do work," she would always say, "that's what men are for." It angered me so. Women certainly weren't useless, like Aunt Evelina thought. Her talk was what sparked me into working at the hospital.

* * *

Mama and I walked out the door and wove our way through the crowd. We had been careful to put on the cloaks belonging to the maids and servants of the house. We knew that the swarming protesters must not see our nice things. Soon, we had reached the hospital. When I first started working, I had gotten frequent nightmares—seeing the once healthy men the way they were was almost a living nightmare. They were extremely thin, their heads were shaved, their beards ragged. But now I had gotten over it. I passed my time re-bandaging the wounds and telling stories of my childhood in the countryside, and it pained me and comforted me to see the happiness in their eyes as I talked about the smell of fresh buckwheat and the many flowers popping up in the springtime. I realized that these men were born to appreciate the wild, raw beauty of the Russian wilderness, and if I were given a choice, I would certainly fight to protect it. I would leave each bed with its occupant promising to tell me of any news about Anton. I knew we were lucky to have Papa still here—he had lost an arm in a war in Manchuria when I was four and wasn't eligible—but I knew that the tsar was getting desperate, and if we weren't lucky, he would soon be drafted.

By the time we got home, the sky was already darkening. When we arrived at the door, Mama quickly put her cloaked arm around me and pushed me inside. Aunt Evelina rushed to greet us. "Anitchka! Anya! Where have you been? The piroshki are getting cold."

"All right, all right, sister," Mama said, "give me a bit of time, dear." Aunt Evelina bustled out of the room, and I saw Mama slip a few rubles into the pocket of the cloak she had worn.

When she saw me watching her, she said, "For a new coat," and together, we walked into the dining room.

* * *

The shouts of more revolutionaries raised me from my deep, dreamless sleep. As I sat up in my bed, I looked over at the window. It was still pitch black. The nights lasted so much longer in the wintertime. I tiptoed downstairs and saw a light on in the kitchen already, meaning the chef was already up. "Anya!" he said. "What are you doing up so early?" I gestured toward the street, and he nodded sympathetically. "Come. I shall make you blini."

Soon after, Mama came down in her nightgown, still yawning. "Anya, how long have you been up? We're working double shifts at the hospital today and I don't want you to be tired!"

"Oh, Mama," I sighed, "I'll be fine."But there was a sudden interruption to our quarrel. "Anya, dear," Aunt Evelina said, stepping into the room in her silk dressing gown, "dark circles under the eyes aren't proper for any young lady."

"Goodness, does everyone have something against me? I shall take a nap before our shift at the hospital." I stomped upstairs, undressed, and positioned myself comfortably underneath the covers. As I lay in my bed, I looked across the room at the dollhouse that had been Aunt Evelina's when she was young. It was an amazing thing, with tiny, meticulous furniture. There was every detail imaginable, right down to the needlework on the sheets of the tiny beds, and I realized that in some ways, the revolutionaries were right. Once my tutor, Olga, had taken me to a factory when we were on a vacation in St. Petersburg, even though she could have been unemployed by my mother for doing so if anyone found out. Olga always wanted me to see the real world and know it for what it was. I had nearly cried when I saw the terrible conditions. Why should some girls get frivolous things, like intricate dollhouses, while others only get one meal a day? This, I thought, I would never understand.

* * *

When I woke up, I was itching to get out of the house and to the hospital. I quickly dressed in an old skirt and blouse, quickly walked out of my room, and ran down the stairs, only to see Mama sitting in the dining room, crying. "Mama!" I exclaimed. "Whatever is the matter?" Wordlessly, she handed me a letter. It read:

Dear Mother and Father,

I will soon be coming home. The German prisoner camp I was in fell apart after the captives rebelled, surprisingly. They put much work into their plan, and thankfully, it worked—I can't imagine what could have happened if it hadn't and the German soldiers had retained control. I would have escaped immediately, but when I was in the camp, a tree fell on my leg and I am currently unable to walk unassisted, so I have been staying at a nearby farmer's house. They will hide me until I am healthy again. I hope all is well with you. Now, burn this letter.

Much love,

Anton

I could hardly contain my excitement. Soon, Anton would come back. He would find some way to get to the city. Then we would go home. At that moment, all the misery of the past months nearly melted away. Somehow, everything would be all right. Later on, as I looked over at the desk in the corner of the room, I could see the tiny red flag Anton had given me so long ago. I thought it would be the last one I would see for a long time.

Seattle, Washington

Katonah, New York