The water. It used to be tranquil. A calm, yet dynamic giant, nourishing the life within. Sometimes its surface churned, purging the muddy banks of debris and stirring up the sediment on the bottom. Other times it was as still as a hot day in August. At these times the mud would settle to the bottom, and the turtles would come to bask on the rocks. The children would run to its edge and catch newts and water bugs. Soon their parents would follow and give the nod, confirming that it was time to play in the refreshing water. Cries of joy would fill the air as everyone was assured that life was good.

This is what I used to see when I looked through the long, tangled branches to our pond. Three-quarters of an acre in area with a small island slightly off center, our pond was a special place where we would all congregate on warm summer days in June, July, August, and sometimes September. The adults would walk down the rough path with cool drinks in their hands and hearty laughs in their throats, followed by the bare and pattering feet of the children. My two sisters, my brother, and I sometimes spent hours in the pond area, frolicking in the sunshine. Often my five cousins processed to the water's edge, where we children would begin stripping down to our bathing suits. The adults would make their way for the lawn chairs on the dock from which they kept a watchful eye on all that was happening.

The first rule at our house was "No matter what, no children may play by the pond without an adult." We followed this rule faithfully but didn't let it spoil our fun. With the adults present, we had races, swam laps, practiced our dives and flips, made sandcastles, and pretended we were mermaids. Sometimes we used the pond for a learning opportunity. Papa would make us aware of the feeding patterns of fish or tell us of the life cycle of the newts at the water's edge. Mama would clear up our uncertainties about sea monsters and whether or not sharks might be lurking in the muddy waters of the deep end of the pond.

In the winter we bundled up like Eskimos and tramped down the slippery path to the pond to try out our ice-skating skills. Occasionally there was a bump or a bruise, but no one let that bother them; there were always a loving mother and some hot chocolate. All we had to do was call.

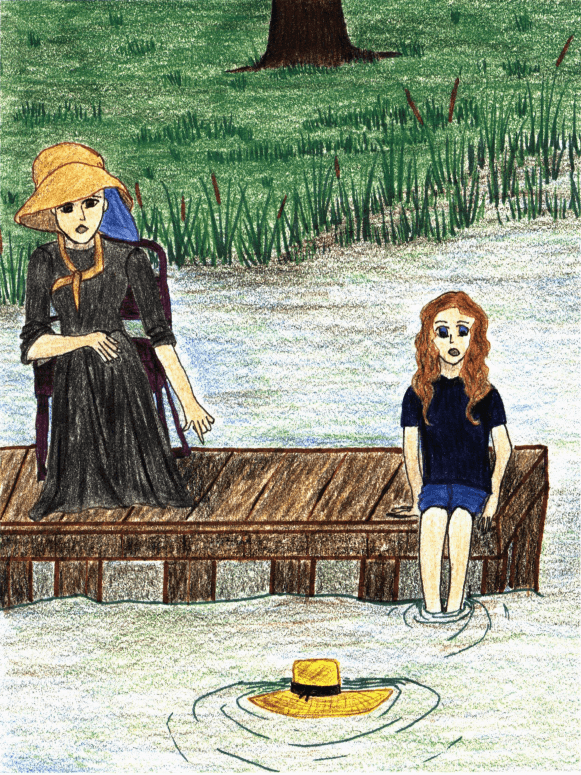

My memories of the pond were nothing but joyous, and I relished every moment of my time there. But on that morning in June, the water transformed before my eyes when I looked at it and saw the lone, straw hat floating at the dock's edge. It was small, hand sewn, with a simple black band encircling the base. The brim? Three-and-a-half inches wide. Carefully cared for, it must have been his Sunday hat. The ripples of water that it made widened quickly, mirroring my fear.

Earlier that morning our Amish friends, the Peacheys, arrived at our home in a big fifteen-passenger van. We had been planning to get together for months. They came on Ascension Day, celebrated by Christians for Jesus' ascent into heaven. For the Amish, this is the only holiday of the year. After lunch and socializing we decided to show the Peacheys our new house. Although it was still being built, it was approaching completion. As we were a big group of people, we went in two carloads. The first group was made up of the men and the older children. As soon as we got to the house, my dad and Mr. Peachey went into the house. Amos wanted a tour. But we children retreated to the sandy beach. There we began building sandcastles and splashing, ankle deep, in the water. It was too cold to go in any deeper.

"This is probably David's first time in a pond," said Sarah, the oldest Peachey child, referring to her younger brother.

I replied, "Really? How old is he?"

"Six," came the response. Modest not only in dress but also in speech, Sarah did not elaborate.

Just six years of age, I thought. This meant he had just started school. He only had one year of English under his belt. No wonder he didn't respond when I called, "Let's go rinse off our feet at the dock and then head up to the house."

Once at the dock, David sat down next to me as we all began kicking in the water. Laughter filled the air. But it all stopped when, after just a few minutes (or was it seconds?), I felt a splash on my leg. Oh, this certainly wasn't the first; we had been splashing the whole time. But this splash was different; it wasn't small and staccato like the rest; it was more like a small wall of water . . . followed by a silence. Instinctively, I turned to look at where David had been and saw only his small hat in the murky water.

"Papa! David fell in the water!" My cry echoed from the hillside. Immediately my dad responded by bounding out of the house with Amos at his heels. As we watched Papa dive without hesitation from the bank into the water, Sarah and I gathered up the other children. I realized that I didn't have any time to waste. I had to do something to help.

Just then I saw Papa's head emerge."Call 911," he said and then, catching a breath, he went back under. I was relieved to have some instructions, but I was also feeling frantic. This big task of calling for help was now on my shoulders.

Running up to the porch, I saw Mama run out of the van and dash into the house. She had come in the second carload, but it was apparent that she could sense that something was wrong. Mama and I met by the phone, and I stood next to her as she dialed those numbers everyone prays never to have to dial. Since Mama wasn't clear on all the details, we collaborated to come up with the facts that the emergency worker wanted. Upon hanging up the phone my mom said, "We have to go flag down the ambulance!"

"OK, Mama. Let's go," I replied.

On our trip down the long lane I noticed that my feet were still bare from having played in the water. The pain of the black macadam as it transferred its stored heat to my tender soles is, for some reason, very prominent in my memory.

"Keep walking," Mama said, breaking my train of thought and taking my mind off the pain. "We can't afford to have the ambulance miss our driveway." I thought about this as we marched on. "We can't afford . . ." Why? What was going to happen? Everything would be all right, just like always. I kept this comforting thought running through my mind as we waited . . . and waited. Everything would be all right . . . right?

"Here it comes!" Mama eventually said.

"Should we follow it?" I replied.

Mama was understandably distraught. All she said in reply was, "Oh, help."

As we followed those red lights and blaring whistles down our driveway, I felt relieved. The outside world was interfering. They would take care of David. At the same time though, it made my heart sink a little. Maybe that's because, now that they were here, my biggest fear was affirmed; this was serious.

Up at the house, the emergency workers leapt out of the ambulance and sprinted down to the pond. I quickly made my way over to where all the other children were waiting in the car. They had been instructed to stay put. When I got there, I found all nine children quiet with fear; nonetheless, the look in their eyes was hopeful. They were waiting for me to bring news. I felt helpless. I couldn't tell them anything, so I just stepped into the car and sat silently in the middle row of seats. As I looked into Sarah's eyes all I could focus on were her pupils. They were like deep canyons with no end. She too was wondering, "Will I ever see David again?"

The commotion of the next few hours was indescribable. I'm not even sure what happened exactly. David was taken by ambulance to the hospital, and for a few glorious moments our hope soared like a bird because news was brought that his heart was beating again. But shortly thereafter we looked overhead and saw a helicopter, and our bird tumbled to the ground. David was being flown to a bigger hospital, which meant things were serious. There they discovered that, although his heart was beating, David was not there anymore. His body was empty. His spirit gone.

Silently I went to bed that night. The tears didn't come. I regret this. Why couldn't I cry. . . simply shed a few tears? It would be the least I could do.

It wasn't until I saw Sarah and the other Peacheys again that I cried. They had lost a part of their family. No one would ever know what he would have done with his life or what potential lay within him.

Now, three years later in the cold winter months, when I walk down to the pond a sharp breeze bites at my cheek, and the mist that rises off the water envelopes me. I turn to look out over the glassy pond surface, and I realize that I am not only looking at a life-sustaining being but also a life-taking creature. A red-tailed hawk cries in the distance, and for a moment I too want to soar above everything and cry out for all to hear.

Alexandria, Pennsylvania