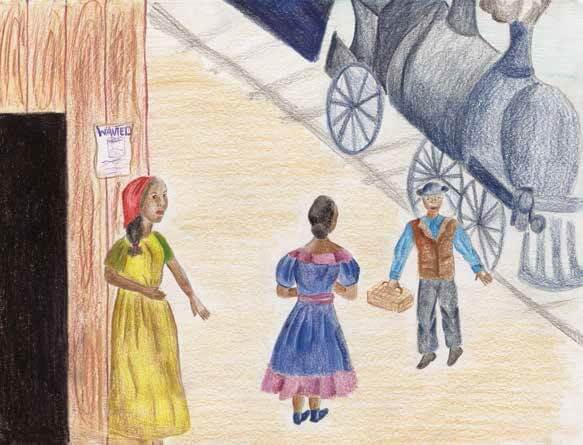

Many Stone Soup readers tell us that historical fiction is their favorite genre. We think we know why. Realistic characters, whose feelings and concerns are similar to our own, can bring the events of history to life better than a dry textbook. A perfect example of historical fiction is “Curtis Freedom,” the featured story from our September/October 2013 issue. The setting is a cotton plantation in the South. The time is the mid-1800s. Curtis is a fictional slave boy who lives during this real time in American history. In the story, Curtis meets the famous abolitionist, Harriet Tubman, a real person. Like many real slaves of the time, Curtis escapes from the plantation with the help of Harriet Tubman and her Underground Railroad. He stays in safe houses along the way and eventually makes his way to Canada and freedom, just like many real slaves did at the time. Thirteen-year-old author Anna Haverly shows us this time in history through Curtis’s eyes, and we experience it with him. It’s unbearable to work in the hot sun and be yelled at by a master who calls you “boy” because he doesn’t even care to learn your name. It’s tragic to be separated from your parents when you’re sold into slavery. It’s terrifying to run away from a cruel master and fear being caught and sent back. And finally, what joy to find your father again in a new land! Did we just learn a lot about history? What a great way to learn, through a relatable character and a story that sweeps us away to another time and place.

Teaching Children

Using Stone Soup to encourage students to produce inventive, creative writing

Creative writing, as a term, was invented in the 19th century to express the idea that there was writing, and then there was creative writing. With use, the expression has lost meaning and now creative writing is synonymous with writing fiction or poetry, as opposed to writing nonfiction. But at Stone Soup we think that it is is important to stick with first principles. Since our founding in 1973, our goal has always been to publish writing by children that is creative in the primary sense of the word: writing that is inventive. A clear problem that we find reading through the stories and poems that are sent to us for consideration by children, their parents, grandparents, and teachers is that so much of the work sent is inspired by reading that it is itself not creative. The source of inspiration for writing that is genuinely creative is life itself. You will find that the stories in Stone Soup tend to be about life – and that is the reason. Ralph Waldo Emerson, one of America’s first great writers, was also one of the first to use the term “creative writing,” and to discuss it relative to reading. In his Phi Beta Kappa Oration of 1838 he said that “There is then creative reading, as well as creative writing.” Creative reading implies a dynamic act, it implies a reader who brings his or her own life to he reading – full engagement. It is the natural way with children to fall into books. Amongst children it is common for the child who loves to read to also be the child who loves to write. It is often true that great writers are also great readers, but it is almost invariably true with children that reading and writing go together. Of course, it is from reading, largely, that children learn to write. The greatest problem we find in reading through manuscripts sent by children (and their parents, grandparents, and teachers) in the hopes that we will publish them, is that so many of the child writers are so clearly readers of writing that is itself not creative. To create is to invent. It it is to bring something fundamentally new into the world, to say something that hasn’t been said, ideally in a way that it hasn’t been said before. Because we are each different, if we each write from the center of our own differentness, then it is not such a tall order to write creatively. The problem comes when we don’t write from the center of our being. One of the biggest impediments to creative writing is the fact that stories and poems are themselves inventions of culture. There are many literary traditions – not all of which are informed by the goal of being fundamentally creative. Clearly, works that are produced for the mass market are, by definition, works in which the goal of accessibility to the largest possible audience takes precedence over the goal of the author speaking from his or her soul. Unfortunately, there is a smaller literature written for children that speaks from the author’s souls than there is for adult writers. And children, I think, are less in control of what they take in than are adults. We adults negotiate the thicket of unlimited options to choose what we want, but we have more agency than children. But what children have is a remarkable closeness to unbridled curiosity, and a drive to learn. That drive to learn is part of the drive to grow up. If you find that your child, or your students, are stuck in writing that is not particularly creative, that their stories and poems rely on formula and cliche or ordinary ways of talking about the world, then you will need to give them a little push. You will find at the Stone Soup website hundreds of stories and poems that we have selected, for decades, out of literally tens of thousands of submissions. The best of what you will find here are transcendentally best, works that reward reading and re-reading. But even at our most ordinary, I think you will find in Stone Soup’s stories creative writing that engages creative readers, and that will inspire your child or your students to reach into themselves to find the words and the way of weaving those words together that genuinely reflects the unique way in which they experience the world.

Writing Activity: using the power of analogy, with “Abigail’s Cove” by Brooke Hayes, 12

Analogy is a very powerful literary tool. It is hard to imagine what it feels like for someone else to have lots of competing thoughts in their head, but when we read this story it is easy to visualize the surf crashing against rocks and from this to understand, at the least, that Abigail has a lot on her mind! Of course, the core of the story is the relationship between Abigail and a wild animal. Notice how Abigail describes in detail what they do together and how she describes her feelings, sometimes using analogy to help us understand the relationship. Brooke uses feeling, descriptions, and analogies (describing one thing by comparing it with another) to establish the reality of the beautiful cove where Abigail spends the summer and the reality of her experiences with Alex, the seal. You can pick out examples of each of these techniques in this short story: Feelings: “Abigail could feel the excitement in her bones.” Description: “The front door was golden yellow, elegantly crafted out of solid oak.” Analogy: “All kinds of ideas collided in her head, like the waves clashing against the barnacle-covered rock.” Project: Write a Story about a Child and an Animal Who Love Each Other Children and animals go together: cats, dogs, horses, rats, rabbits, hamsters, and mice are some of the common animals who make friends with children. Like Brooke, clearly establish where the story takes place. Use as much detail as possible to let your reader visualize the scene. Remember that, in addition to seeing, smell is often important to us, as are feelings–how the sand feels between our toes, for expample, and how we feel emotionally about where we are. At the core of the story, though, should be the relationship between the main character and an animal. Describe what they do together and how they feel about each other. Notice how Brooke keeps the seal acting seal-like. Brooke’s seal is not a human. The seal moves and acts like a seal! Your animal friend should act like the animal he or she is. Describe movements and motivations that are consistent with a cat or a dog or a mouse or a squirrel or whatever animal you choose as your character’s friend. Abigail’s Cove Written and illustrated by Brooke Hayes, age 12, from Bangor, Maine From the March/April 1994 issue of Stone Soup ABIGAIL COULD FEEL the excitement in her bones. She knew that this would be the best summer ever. Abigail was returning from Detroit, Michigan. Her father had been transferred from Islesboro, Maine. Abigail’s father, Mr. Will M. Jeffers, is an architect for the company Bradford O’Day. Abigail’s mother, Mrs. Lynn A. Jeffers, is an attorney for the firm Johnson and Murphy. The two-and-a-half-story white house sat on high ground, peacefully overlooking a stretch of land that led down to a small cove. The old country house was framed with black shutters that shone like quartz in the sun. Jutting out from the window sills were flower boxes that cradled crimson-red geraniums with soft and delicate petals. The front door was golden yellow, ele-gantly crafted out of solid oak. If you were to sit at the living room window, a breath-taking view would enve-lope you. The big stone fireplace was always aglow on cool, damp days. Abigail breathed in the salty air as her toes tingled in the cool waters of the cove. Ashley, her twin sister, was already in the water. Abigail ran into the house and tried to squeeze on her old black-and-white-striped bathing suit. It was just too small. With disappointment Abigail scurried to her mother’s bedroom, where her mother was in the midst of unpacking summer clothes. Abigail explained her dilemma and Mrs. Jeffers suggest-ed a trip to the mainland on the ferry within the next few days to buy a suit. Abigail felt her bubble of excitement and fun pop like the air dribbling from a balloon. She dragged her feet to the wharf, tripped, and clumsily fell. What a great summer this was evolving into, she thought. Just as she sat down, feeling sorry for herself, something cold and hard rubbed against her skinned shin, tickling her knee. She couldn’t imagine what it could be. All kinds of ideas collided in her head, like the waves clash-ing against the barnacle-covered rock. From out of the gray-green water popped a white head for just a few sec-onds. Abigail sat very still in amazement, hoping that this slippery creature would re-appear. With a splash he did. Abigail spoke gently to the young seal. The seal seemed to understand that Abigail wanted to be friends. He barked and wiggled with joy. The horn on the ferry blasted upon its arrival to the island, frightening the young seal back into the sea. Abigail sauntered home, retreating to her cove, wondering whether she would encounter the seal again. Abigail would not share this special event with anyone except the gentle waters of the cove. The next day, at the same time in the afternoon, she sat very quietly waiting for the seal to appear alongside of her. In no time he did. Abigail patted his sleek fur coat as she gazed into his big black eyes. She whispered to him, “Alex.” Each day Abigail would rendezvous with Alex and bring a bucket of fresh fish, their love and friendship blossoming like wild roses in the ocean air. To remem-ber this budding friendship Abigail was carving a seal out of driftwood she found in her cove. One evening, having spent a lovely day in the cove and sharing special moments with Alex, Abigail plunked herself down next to her father to watch the news. An alarming weather forecast interrupted her feelings of tranquility. A severe hurricane watch was in effect. Hurricane Chad was moving toward the coast of Maine and it was anticipated to hit Islesboro within the next twenty-four hours. Abigail’s first reaction was, what will I do with Alex? She did not sleep well