Interview with Blandine

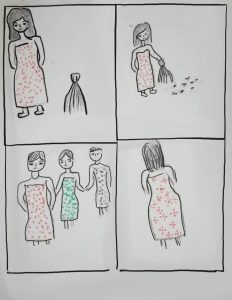

Thank you for sharing this powerful story with us. Could you tell us about what inspired you to write it?...

Read More →

Read More →