The light glinted playfully across my face, awakening me from my slumber. I reluctantly got up from my warm, furry haven curled up beside my mother with all of my siblings around me. I stretched luxuriously, and winced as I remembered yet again how hard the floor of that cave was. Cautiously, I tried to crawl over Hashim, who had odd brown stripes across his forehead, and Malishkim, with the white paws, without waking either of them up. I warily crept up the natural stone stairs that circled their way around the inside of the cavern and peered into the shallow freshwater lake in the room at its zenith. The reflection that looked back up at me didn’t look anything like the faces of my family. My face was tanned from the sun, but it was still starkly naked and pink. Everyone else in my pride had rich, deep golden fur over their entire bodies, and the papuas, or fathers, in our pride even had a long brown fringe of fur around their faces. My hind legs were much, much longer than theirs, and I had peculiar miniature extensions with tough plates at the ends of them coming out of my paws. The reflection that looked back up at me didn’t look anything like the faces of my family I splashed awkwardly into the water, transforming my reflection into a plethora of tiny ripples. I liked it that way. I couldn’t see that I was different. I began to wash. It wasn’t always like this. My moshi (mother) found me under a bush in a mirage when I was very young, crying louder than she had ever heard her own young yell. I was a hideous, Crimson, wrinkled tiny thing covered with a strange-colored fur that wasn’t plush at all. But Moshi felt an unusual sense of compassion for me, and she had finished her hunting for that day already anyway, so she gently placed me on her back and took me to her pride. When all of the papuas in our pride came home, not everyone thought that I should be welcome. However, my moshi and papua insisted, so they brought me along with them from shelter to shelter. The others had to listen to them because they were the leaders of our pride. “Lalashim? Are you up there?” My moshi’s melodious voice awakened me from my daydream. I quickly licked my paws and ran them through the long, red fur that only grew on top of my head. I stretched and finally ran silently down the steps. All of the moshis in our pride were looking up at me expectantly from the foot of the stairwell. The sun was showing its full, round, orange face, a small hoofka above the horizon, so it was time to go hunting. The papuas and cubs were still sleeping, as they would until they saw it fit to rouse themselves. We all slunk out of the cave into the bright, warm morning. I loved waking up early to go hunting with the females. Everyone walked along in a comfortable silence until we caught the scent of an antelope, Zebra, or other hefty animal. The giraffes we left alone, though. There was an old legend saying that if anyone tried to sink their teeth into their supple flesh, they would move their powerful legs and kick us to join our ancestors in the heavens. Then, we would creep up as close as possible to the animal, and when we were sure that we were at the most advantageous spot, we would run simultaneously up to prey and trap it until one of us could clamp our jaws on their neck, the fatal spot. There would be a small struggle, but eventually the animal would succumb to death and hang limply in our mouths. Finally, we would eat until we were full to bursting and bring what was left home. This was where my job would come up. Two summers ago, I discovered that the sticklike objects protruding from my paws could curl around a kill and make carrying the meat much simpler. Since my legs couldn’t move swiftly enough to trap our meal, my teeth weren’t sharp enough to cut its throat, and my nose was too feeble to smell the animal, I insisted to the other hunters that my task would be to carry the kill back home. That day, we were all chattering cheerfully on the way back. It had been a good hunt; we had brought home three zebras and two antelope. Suddenly, my moshi stopped in her tracks, her muzzle raised high and twitching. “Humans! Upwind from here!” she exclaimed. We all swiftly turned our heads upwind. As one, we skulked from bush to bush, out of sight of the humans, until we could see them. It was rare that people ever came here to the savannah because the climate was so harsh. Being that we were all very curious creatures, when they did come, we always went, unnoticed, to check them out. We never attacked them unless we were particularly desperate for food or they were disrespecting our space. As we all crouched under a patch of dry grass, we inspected them painstakingly. These particular ones looked very strange. Most of the humans who came here were very dark. Moshi says that they are the native humans of this land. But these, these humans had oddly pink skin, so light they were almost white! There were two of them; one of them had long, red-gold hair and sparkling blue eyes, and the other had short, deep brown hair and greenish eyes that looked rather like the deepest part of the hidden pool in our cave. And yet . . . they looked vaguely familiar, like a memory from a dream. One of our youngest moshis, Ganua, blurted out precisely why I remembered them. “Why, they look like you, Lalashim! Especially the one with the orange hair!” I

Little Mango Tree

Jiraporn looked up. Mother was approaching, shaking her head. “Bad news, Little Mango Tree. I talked to Bouchar. He says we lose the house unless we pay the remaining mortgage in one month.” “But so much money!” Jiraporn protested, hugging herself. “We can’t harvest enough rice to pay that, let alone feed ourselves and the spirits.” Mother nodded dismally, and sat down next to Jiraporn. Gently, she pried the knife and half-peeled, slightly ripe mango from her daughter’s fingers. “I don’t like to see you with a knife, Jiraporn. You might cut yourself.” Jiraporn’s soft, dark eyes restlessly watched her mother’s hands wield the knife, sliding the dull, silvery blade across the scarlet-gold fruit in a peeling motion. “But Mother, I must help somehow. You let Vichai work the plow.” “Well, he is much older than you,” Mother stated primly. Vichai was seventeen, three years older than Jiraporn. She paused a moment in her peeling, then stood abruptly and strode away across the smooth dirt. “Go work on your math homework, dear,” she added over her shoulder. Jiraporn’s eyes grew moist and shiny, and she clenched her fingers in her loose black hair. Yes, she could go do her algebra while her whole family starved and lost their house and rice field. She tilted back her head and looked up into the shady branches of the kiwi tree. “But I would rather die than be idle and useless,” she murmured to their rustling, sunlit leaves. A cicada chirped nearby, and a large cricket alighted on her navy blue skirt to rub its silken wings. “Next,” Jiraporn confided to the cricket, “she’ll be locking me inside.” Jiraporn’s eyes grew moist and shiny, and she clenched her fingers in her loose black hair Sighing, Jiraporn stood up, brushed off her clothes, and hopped onto her brother Vichai’s bicycle. Pedaling with her feet, she gripped the handlebars and steered it over the dirt in front of her house to the narrow path that led to the market. The wheels spun slowly, bumping over loose stones and gravel, jostling Jiraporn from side to side. Yet she was relaxed and confident. It was not the first time she had taken her brother’s bike while he was away in the fields. And she had pinned a note to a banana tree so her mother wouldn’t worry any more than she always did. “Jiraporn!” Visit exclaimed when she pulled up beside his stand and got off her bike. He grinned. “Off on your own again?” Jiraporn shrugged. “I need help, I guess. What are you selling today?” she asked suddenly, avoiding the subject. “Scallops?” “Nah, carp. Got the best here in all of Thailand.” He gestured to the wooden bins of fish. “You must really be distracted to mistake carp for scallops.” “So I’m blind,” she said carelessly. “Just one more thing to worry about.” There was a brief silence and a man walked by, selling cotton and banana bunches. At last she said heavily, “The truth is, Visit, Bouchar is taking our house away if we don’t pay by next month. We promised two months ago to pay, but we just don’t have that much money.” Visit’s wrinkled face was grim. “Nasty landlord. How much?” She told him. “I need a plan. A good one. I do all this schoolwork that’s supposed to make me smart since Mother won’t let me work, and now I have a chance to put it to use and I can’t think!” Jiraporn buried her face in the white cotton sleeve of her blouse. Visit sighed and patted her back. “Maybe I can cheer you up. It’s not much, but . . .” he wrapped two fish in some greasy brown paper. “Take this home to your mother. By the way, that Anna Kuankaew came by the other day.” Jiraporn nodded absently, stuffing the fish into a wicker basket nailed to the bike’s handlebars. Anna Kuankaew was a rich lady who had come by once, wanting to buy their mango tree, but Jiraporn wasn’t really interested. “Thank you!” she said with sincerity, pedaling off. “Wish I could help!” Visit called after her. “It’s outrageous!” exclaimed Mother in anguish when Jiraporn slipped quietly into the kitchen. Mother set a dish of steamed rice and prawns on the table and put her hands on her hips. Jiraporn stood, still and solemn, for a moment before going to place the parcel of fish on the table. “Explain yourself,” Mother commanded angrily. “How dare you ride a bike, you could have been overturned and died!” Calmly, Jiraporn said, “Visit gave us some fish.” “Take it back,” snapped Mother. “I’ll not be accepting charity.” “It’s not charity, Mother,” put in Vichai from the corner, sitting down cautiously on a low stool, “it’s a gift.” Shaking her head, Mother sighed and placed a pitcher of coconut milk and some sliced mango beside the prawns and rice. Seating herself, Jiraporn poured coconut milk into her cup and put food on her plate. They ate glumly, in silence, except for one point when Mother, wiping her mouth on her apron, muttered, “If your father was alive everything would be fine.” Lying on her mat that night, staring at the filmy gray mosquito netting that floated beneath the dimly burning lantern, Jiraporn wondered sleepily what it was like to make a difference. The next morning was hot, and Jiraporn opened the door to let some fresh air in as she cooked a simple noodle soup with mushrooms. Mother entered with an armful of bananas. “Sorry about yesterday, Little Mango Tree. I ‘spect it’s on account of that money.” She dabbed at red eyes and sniffed. “‘Fraid I cried a great deal last night.” Dropping her spoon, Jiraporn bent over and comforted her mother, hugging her. At least that was one thing she could do. As she drew back, Mother set the bananas down and started making tea. After a moment, Jiraporn begged, “Please let me harvest rice, Mother.” Mother

Patches of Sky Blue

When my mother died the summer I graduated seventh grade, the first thing I did after silently returning home from her funeral with my father was dig through my trash bin in search of a previously ignored leaflet distributed by our local Parks and Recreation. I then signed myself up for every class, workshop and camp they had listed. If my father was mystified or annoyed by my actions, he kept it to himself. Perhaps he was so overwhelmed by his own grief that it didn’t strike him as odd at the time. I also plastered my bedroom walls with the activity schedules for each class until there wasn’t a square inch of wall that wasn’t completely covered. It became an obsession. I attended each class religiously, never missing a beat. It took me from sunup to sundown every day and gave me a reason to get out of bed in the morning. I stayed up late into each night working on this or that small class project. The classes I took covered a whole range, from kayaking to keyboard to cheerleading to modeling. In art I painted pictures of daisies and smiling fairies. I wrote poems in a kind of singsong rhythm about balloons and happy cows. There was nothing I was doing that even hinted at my loss. Something would have to break me and my newly focussed life because it was all an act. I lived like an actor who can’t get out of character and leads a kind of half-life. No one seemed to understand me anymore, myself least of all. “Elle, you’ve never had trouble getting started. Why the exception today?” It happened in poetry class. I had been just about to hunker down for another three-hour session, and had a particularly sugary first line in mind when Mrs. Tucker, the instructor, made an announcement. “Today we’re going to have a special assignment, we’re going to write about some things that make us sad. Any examples?” She looked around cheerfully, her watery blue eyes slightly magnified by rectangular glasses. She was the typical well-meaning but clueless teacher. She didn’t seem to see the irony in her merry expression as she repeated the assignment: “Write about something that makes you sad” . . . smile . . . something that makes you sad . . . She had started to pass out the papers when I asked numbly if I could be excused to go to the bathroom. She smiled. “Yes, you may.” I slipped out the door into the main hall of the YLC or youth learning center where the class was held. I didn’t go to the rest room, though. I just leaned against the wall and stared at the ceiling. I had been there longer than I had thought because suddenly my teacher was there, bending over me, and looking anxious. “Elle, are you all right? I thought you were just going to the bathroom . . .” She looked at me as though expecting an answer; an answer to what? Did she think I knew every little thing about myself?!? Wait, I was being stupid. This was a simple question. The answer wasn’t simple but at least I could give the answer she was expecting to receive. “Yes, I’m fine,” I said. “Good.” She looked satisfied as I followed back to the classroom, noting how her walk resembled that of a duck’s. Ducks seemed like a good subject for a poem. Then I remembered. My assignment was to write a poem about something sad. Instead of writing, I drew a cartoon-like duck wearing a purple vest (not unlike the one she had on). Then I sketched a cartoon of the actual Mrs. Tucker. Mrs. Tucker wandered aimlessly around the room, every so often saying things like “Good job!” and “A nice beginning.” Even when she criticized, she beamed as though she were saying something nice. When she stopped by my desk, her smile flickered and she drew her penciled eyebrows together in a look that might have been annoyance if she hadn’t maintained a partial smile. “Elle, you’ve never had trouble getting started. Why the exception today?” How could I answer that? “Ummm,” she peered closer at me, “yes . . .” “It’s. . . hard,” I offered thickly. She relaxed her expression and sighed. “You should have said you were having trouble, I could have helped you sooner.” She got down on her knees so her face was level with mine. “Write down five things that make you sad,” she said. “I don’t know.” “I’m sure you can think of something; everyone is sad sometimes.” “Not me.” After I said this I realized both how childish it sounded and how utterly untrue it was, but I kept my mouth closed. “It’s not a bad thing. Everyone . . .” I cut her off. “I said nothing makes me sad, and I mean it, OK??” She suddenly became uncharacteristically crisp. “I don’t believe it. You were sad when you forgot to do your homework that one day. You said, ‘Mrs. Tucker, I’m very sad that I forgot my homework.’ You said it, I heard you! I rememb- . . .” Then it burst. All the fury and fear and grief and even guilt that had been silently smoldering inside me these past months burst. “Do you think that’s what real sadness is?!?” She looked taken aback. “Well, I . . .” “Do you??” My voice rose to a pitch. The other students started turning on me, looking annoyed, and alarmed and even . . . sad. Suddenly my pen flew to the paper and my hand started scribbling down words faster than my mind could take them in. I wrote about metal screeching against metal, muffled screaming, flashing red light reflected on water-drenched pavement, dark silhouettes being carried past on stretchers. Then there was fluorescent light shining on bare white walls. A naked light bulb, bathing everything in a blinding glow.

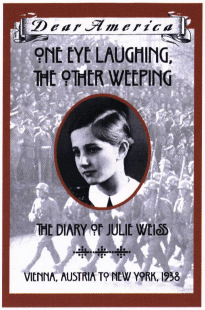

One Eye Laughing, the Other Weeping: The Diary of Julie Weiss

One Eye Laughing, the Other Weeping: The Diary of Julie Weiss by Barry Denenberg; Scholastic, Inc.: New York, 2000; $12.95 When someone says the word “Jewish” do you feel a sudden rush of hate, a thrill of fear, or does it even stand out enough that it makes you feel anything at all? For Julie Weiss, a Jewish girl who is about twelve years of age, that word means fear and confusion. One Eye Laughing, the Other Weeping is a book about the Holocaust. A book about the astounding measures the Nazis took while trying to banish the Jewish culture. Julie experiences the horrors of the Nazis, firsthand. This author does an amazing job of creating a young girl that is just like the children today. Julie worries about growing up, making friends and going to school. But then one day her world is shattered. The Nazis take over Vienna and suddenly there is more to her life than just fun and games. Now, she has to worry about whether or not her life and her family’s lives are in danger. Friends turn into enemies and respect turns to hatred. The Nazis chant in the street, “Kill the Jews, kill the Jews!” Is it possible that they could kill Julie? Julie is immensely confused. Why is it that suddenly Jews are thought to be terrible monsters instead of just human beings? Before Hitler had entered Julie’s life she hadn’t thought anything of her religion. Her family never went to the synagogue, never prayed and never thought very much about God at all. So, why is it that suddenly she is thought to be this disgusting thing that everyone hates? Could it be that the only reason that she is considered Jewish is because Hitler says she is? This book is portrayed to you in fascinating diary entries. One night Julie writes about when the Nazis barge into her home. As the Nazis go through her family’s house, throwing things out of windows and destroying everything in sight, Julie sits silently in fear. Then, suddenly her brother and father are yanked out of the house. Outside, they are forced to scrub the sidewalk to rid it of anti-Hitler signs. Eventually, the men and boys realize that the liquid they are scrubbing the sidewalk with is not water, but a kind of paint stripper that burns their hands. If they stop scrubbing they are punished severely. Many other events like that one are referred to in the book. One man who refused to do as the Nazis ordered had gasoline poured over him. Then, they lit a match and as the man protested and screamed that he would do anything the Nazis wanted, he was burned to death. The author, Barry Denenberg, tells the truth, plain and simple. Although I cried at many times throughout this book I am glad that I have finally found a children’s book that tells the unvarnished truth. One Eye Laughing, the Other Weeping will tell you what really happened in those years so long ago. It will not hide the story behind curtains of lies. I have read many books about the Holocaust, but none were quite as moving as this one. Thankfully, I have never experienced the constant fear that Julie must have lived with every day, but when three buildings were attacked by terrorists in the United States I experienced as much fear as I have ever felt in my entire life. Though no one I knew was hurt or killed there, the thought of all those who were chills me to this very day. The fear that most American citizens felt on September 11, 2001 was a small taste of what so many people who lived during the Holocaust had to survive with day in and day out. As Barry Denenberg weaves history and the life of an ordinary girl together, this story comes alive. Suddenly, you’re reading much more than the diary of an ordinary, young girl. You’re reading a book about human cruelty and human kindness. You’re reading a book about something real that may have happened to your ancestors. Read this book to find out what will win in Julie’s story, evilness or goodness? Cassy Charyn, 11Bainbridge Island, Washington

The Ocean

I stand on the ocean shore, watching the waves go by. The sun is going down but I don’t leave. I will stay out on the ocean shore. Seagulls fly overhead, they land down on the beach. Their far-off cries bid the day good-night. Out in the sunset I see dolphins leaping through the waves. Their turning, jumping transforms the setting sun into the start of a new day. They call out to me and I long to join them in the freedom that is the sea. Sunset is a dark, purple haze, recalling everything that is beautiful. I grab a boogie-board and float along with the water. A giant wave comes over me and I tumble head over heels underwater. In the sea I am a new creature. When I return to the surface I laugh out loud. I look up and see the first stars. The sky is becoming black. It is time for me to be going. Tomorrow I’ll come back and watch from the ocean shore. William Ilgen, 9Berkeley, California

The Land

The Land by Mildred D. Taylor; Phyllis Fogelman Books: New York, 2001; $17.99 “Can’t figure how you can be so crazy ’bout them white brothers of yours neither, when once y’all grown, they’ll be the boss and you’ll be jus’ another nigger.” One of the factors that made The Land so interesting was a unique conflict. Paul-Edward grew up with a black mother and a white father during the post—Civil War era. There was still a good deal of hate between the two races in the South. Though slavery was illegal, blacks were still treated like dirt. As Paul-Edward was growing up, he was the proverbial “man without a country.” Blacks didn’t like him because he had white skin and whites didn’t like him because they just knew that down deep he was a black. As I said earlier, this presented a very unique conflict. Another reason that The Land was so good was that it played my emotions better than Yo-Yo Ma can play the cello. When Paul was trying to win the horse race, my blood pressure rose higher. When Paul was missing his dad because of running away on the train, the next time I saw my dad I hugged him tighter. When Paul was running from the whites, I pulled my bed covers a little closer. The two main characters are Mitchell, a black who starts out hating Paul-Edward, but eventually—through a deal with him—becomes his best friend. Mitchell isn’t afraid of anything, and has a great sense of humor. The other main character, of course, is Paul himself. He is very intellectual, has a healthy amount of worries, and doesn’t understand why whites hate blacks. These characters’ clashing personalities give the book pizzazz and bring two, usually opposite, views of each situation into the mix, making it a lot more fun to read. Most people would say this book is simply preaching against racism, but the moral goes deeper than color. The Land is not just simply about blacks vs. whites, but it tells a story of how through friendship, love, and determination a man beat the odds and made his dream a reality. It doesn’t matter if it’s a black who wants to own land in a white man’s country, or a boy who wants to become president when he grows up, the moral is that nice guys don’t necessarily finish last. The Land is fast-paced, a quick read, and very well written. I normally do not even enjoy historical fiction, but this was one of the best books I have read in a while. Sam Gates, 13Louisville, Kentucky

Mystery at the Marsh

“Look!” A little brown head bobbed out from under the dock; the feet under it propelled it around the reeds and out of sight. “What was that thing?” asked Ted, almost falling into the water trying to find it. “A muskrat, kids. You can use that in your essay when we get back to school,” said Miss Cole. Ann Dover looked out at the ripples shimmering and glistening with the reflected sun. She sighed, her breath sending a gray smoke-like puff over the lake. The gently swaying cattails rustled and Ann caught a whiff of the dusty incense they gave off, tickling her pink, cold nose. “OK, class, you may start taking notes now.” Ann stared into the water. The bottom was covered with long, stringy algae, which she assumed was making the almost-faint stench. It looked cold and lonely, but Ann knew it was full of life. “Full of life,” she wrote. As Ann looked back at the warm biological station, she noticed something by the bank. It was a big pile of what looked like algae, but it was more clumpy, like individual things. She started to examine it, but out of the corner of her eye, she saw her teacher looking disapprovingly at her, and quickly started writing. “OK, kids, pack up. It’s snack time!” It looked cold and lonely, but Ann knew it was full of life Ann heard people hiss, “Yesssss!” under their breath. Everyone got up and formed a line. As they trudged back up the dock, stomping their feet to warm them, Ann heard Bob whisper to Jeff, “Finally. It smelled like dead fish over there.” Dead fish. That was what the pile was. But how did all those fish die? Ann thought. Best not to think about that now, she decided. All she was thinking about was having a nice snack in the warm biological station. * * * Ann was relieved when the class stepped in front of big doors leading to a warm, cozy habitat. Everyone wanted to get in, and there was a scramble as the doors of the biological station opened. Along the wall were all sorts of stuffed marsh birds, displays of life cycles, and glass cases of rock samples marked with little labels. Off to one side, there was a little shelf. In it were eleven or twelve species of fish. Fish. Ann caught up with her class and seated herself against the wall. After unzipping her backpack, she took out a fruit rollup. Dead fish. True, it was still cold from the winter that had passed, but they should have been hibernating, or whatever fish do. She would have to look around the lake again. Sitting up, she saw a little plate that said “Men’s Room—205. Women’s Room—128.” The women’s room was downstairs! She could ask to use the bathroom, and then slip out the door that led to the lake. Getting up, she walked over to her teacher. “Miss Cole, may I use the bathroom?” Ann held her breath. “Hurry back. We’ll be working on the trail next.” Rushing downstairs, Ann started searching for the lake door. She had only seen it from the dock, and it wasn’t a main door. “Hi!” Ann glanced up. Looking down at her was a kind-faced woman in a scientist’s white lab coat. Her name tag read Biologist Mason. “May I help you?” she asked. Ann thought quickly. “Could you show me to the bathroom?” she asked, hoping her face didn’t give her away. “Right down the hall, and through the third door on the left,” the woman answered. Ann thanked her, and started to the bathroom. “Do you like the lake?” she heard Biologist Mason call after her. Ann turned around and nodded, trying to make it look like she was in a hurry. “Come with your family sometime, and I’ll show you around. My name’s Jennifer.” With that, finally, the biologist turned and retreated into a lab. Ann stood a moment, thinking. Then, she realized how little time she had. Stepping down the last of the stairs, she looked right. There was a lab. She looked left. There was a big door propped open by an oar. Ann pushed open the door and stepped out onto a dirt path. A little to the right stood the dock. Ann ran out to where the fish were. It hadn’t changed from a few minutes ago. There was nothing she could see to cause the fishes’ death. Crushed, Ann turned around; she was face-to-face with Jeff Schiller, one of her seventh-grade classmates. Ann stared at him. Then, knowing they would both get in trouble if they were late, they started walking back. “You’re going to tell on me, aren’t you,” Ann said without looking at him. “No, I was coming out for the same reason. To see about the fish.” Seeing Ann didn’t trust him, he added, “We can find out together.” “OK,” Ann said. “But not now, we’ll be late. I’ll talk to you at break.” She immediately regretted it, but there was no time to take it back. Jeff followed her as they ran up the stairs, clanging on the metal, making an echo loud enough for the world to hear. * * * “Rinnnnnnng!” Back at school, break time had finally crept its way up to pounce on Ann. She looked around, but in the mass of kids, she lost sight of Jeff by the door. Slowly, she slipped her essay paper (titled “Wingra Marsh”) in a blue folder and, putting her pencil back in her desk, got to her feet. Other girls have crushes on boys, but not me, she thought, staring at the door. What will people think when they see me talking to Jeff—the most popular boy at Henry James Middle School? She took a deep breath and started outside. “Ann.” Ann jumped. She had forgotten about Miss Cole correcting papers at her desk. “May I see your essay, please?” “Oh,” Ann

Esperanza Rising

Esperanza Rising by Pam Murioz Ryan; Scholastic Press: New York, 2000; $15.95 Did you know that esperanza means hope in Spanish? That word, and that word alone, is the perfect way to describe the young heroine of this novel, Esperanza Ortega. Esperanza Ortega is a pampered little rich girl in Aguascalientes, Mexico in 1930, who has all the food, clothes, and toys that any twelve-year-old child could want. She has many servants and she has her love for her mother, father, and grandmother. The novel starts by showing the theme of the book: when Esperanza was six years old, her father took her for a walk in El Rancho de Rosas, their home, and told her to lie down in the field, and she could feel the heart of the valley. When Esperanza did as he said, it turned out to be true, and she and her father shared this little secret. The day before Esperanza’s thirteenth birthday, however, a horrible thing happens: her father is attacked and killed by bandits, who believe that they killed righteously, because Papa is rich and most likely scorns the poor, like them. When this dreadful news is delivered to Esperanza and her mother, they go into mourning, and Papa’s older stepbrothers, Tio Marco and Tio Luis, come to supposedly help them through their time of need. The true purpose for their staying comes clear, though, when Tio Luis announces that he wishes to marry Mama. However, Mama turns his proposal down. But after the uncles burn their house to the ground, the family realizes that they must leave Mexico. Esperanza, Mama, and their former servants—Miguel, Alfonso, and Hortensia—take the train to California and begin to work as farm laborers. Esperanza is enraged, however, because she is not used to “being treated like horses” or living among poor people. Even after she befriends Miguel’s younger cousin Isabel, she still scorns and fears the labor camp because there are the strikers in it who are trying to get better working conditions and will stop at nothing and no one to get what they want. I liked Esperanza Rising, but there was one big thing that I didn’t like: Esperanza was so real a character that I felt a little bit queasy. I’m not very comfortable around realistic fiction books. I’m more the fantasy-novel type. I still don’t like books that don’t end “happily ever after.” There were some things that Esperanza experienced that I have as well. When Esperanza was asked to sweep the porch and she didn’t know how to even use a broom, I knew just how she felt, because I’ve had that feeling more than once. When I was little, I begged my mom to let me have a bike, so I could be “just like the big kids,” and I never rode it, so I’ve never learned how to ride a bike. When my friends ask me to ride my bike with them, I always have to lie and say that it’s “much closer to walk,” and “oh, couldn’t you walk, too?” It’s very difficult when you can’t do something that most other people can. But Esperanza learned how to use a broom, while I still have yet to learn how to ride a bike! Esperanza Rising is written so you could definitely feel what the characters were feeling. I very nearly almost laughed out loud at the part when Esperanza had to wash the babies’ diapers and she didn’t know how, so she was just dipping them into the washing basin with two fingers. Esperanza Rising is a vivid, well-written book. The author takes her time, and describes every scene and every character as though the whole novel revolved around them. And she shows how Esperanza changes: from a pampered, stuck-up girl, to an understanding young woman. And the whole story contains hope. Hope that the strikers will understand why Esperanza and her family and the other workers need their jobs and will not join them. Hope that Esperanza will one day become rich again. And hope that Abuelita, Esperanza’s grandmother, will one day come and join Esperanza and Mama in the labor camp, because she was left behind at El Rancho de Rosas. Luisa V. Lopez, I INew York, New YorkLuisa was 10 when she wrote her review.

Paradise

I look once more out the rolled-down window of our faded blue Chevrolet and gaze out at our little yellow summer house, rapidly shrinking as we roll away. The trim white shutters are pulled tight, awaiting next year when we return and the house will brim with life and energy once again. I see our dark auburn porch sitting peacefully on the sand. A warm breeze blows, tinkling the silver chimes that hang from its roof. The little windowbox my mom uses during the summer has nothing left but a little dirt and maybe a couple of dead spiders. Stretching below and past the porch is pure white sand. It leads to sparkling aqua-blue waters that reflect the sun and almost blind me in their brightness. I remember this morning when I took a last swim in the cool, turquoise waters. The sunrise was beautiful, pale pink, lavender, and apricot, but the water held a chill which I hadn’t felt all summer. I remember this morning when I took a last swim in the cool, turquoise waters I look down at my patched denim cutoffs. They have been worn so many times that they are almost white, but they hold a faint sea-smell that I love. Those shorts bring back memories of all the past summers we have spent on Richolette Beach. I remember the sunny day a few years ago when a bunch of neighbors and our whole family teamed up to push a beached whale back to sea. I recall that notable time when Dad first taught me how to sail a boat. I remember watching my first falling star on Grandma’s knees late one night, catching my first fish, and learning the miracle of life one week as I watched hundreds of baby sea turtles, just hatched, crawl to the sea for the first time. Mom reprimanded me this morning, saying that it will be cold back in San Francisco and I should at least wear pants, but I insisted that since it was the last day of summer, I was going to wear my summer shorts. The last day of summer. I guess I can’t deny any longer that fall is really coming. The leaves of the oaks and maples we drive by remind me of colorful nasturtiums and flickering flames with their brilliant reds, oranges and yellows. I look back longingly at my lovely days of getting up early for a refreshing morning swim, sunbathing idly on the soft, warm sand, and hunting for interesting shells for my collection. I remember watching the sun set over the ocean and then dropping into bed, exhausted but exhilarated, to fall asleep to the peaceful sounds of waves lapping playfully on the sand, and crickets chirping soothing lullabies. Realization creeps over me that starting tomorrow I will again be forced to stick to a strict schedule of homework, teachers and classes. I shudder slightly as a cool wind sweeps through the car window, which I close. Forcing thoughts of school to the back of my mind, I lean back cozily against the warm seat and close my eyes. My mind wanders freely, and again I start daydreaming of past days at the little house on Richolette Beach. For I know that summer will come again, and I will once more lie on the sand, idly watching the gentle waves. I know that once more, I can be in paradise. Leah Sausjord Karlins, 12Campbell, California Maya Sprinsock, 9Santa Cruz, California

Characteristic Property

The space pods zoomed above Cassiopeia Jaiden Starwing as she stood on the moving sidewalk on her way home from Academy. Cassie ignored the zooming noise as everyone else did, but her mind did not focus on the obvious. Cassie always acted mellow—she was the youngest of seven children, and the only girl, and she was used to lying low while her brothers got into trouble. But today Cassie was bubbling inside. Tomorrow was her thirteenth birthday, but, like everyone on the planet Earth, she celebrated a day before with her family members. Today was her special day—her day to shine. Cassie grinned as the sidewalk approached her home. It was common knowledge throughout the galaxy that the people on Earth had some of the richest homes anywhere—Earth was a base station to the other planets and jobs there were well paying and important. Cassie’s home was no exception—it was a huge house, with floor upon floor of circular living space. Cassie’s father owned the fastest growing rocket ship company in the galaxy, and was always busy. Cassie’s mother used to work for the Intergalactal Peace Council and retired soon after her second son, Forrest, was born. Now Oriana Starwing was one of the most admired economics teachers on Earth, and was known as far away as Neptune. The space pods zoomed above Cassiopeia as she stood on the moving sidewalk Cassie entered her home, expecting to be greeted by her family at the door, the way her brothers’ celebrations began, but things were not as she suspected. In fact, they were the opposite. Her mother rushed around, collecting papers and briefcases, her pretty blond hair pulled off her face, exposing her Martian features, a skinny pointy nose and a heart-shaped face. Her father, unusually harried, barked instructions into the videophone in the living room. Cassie could see he was talking to his secretary, the chubby one, and an immigrant from Venus. Something about his wife going away . . . needing a housekeeper . . . “Cassie, star beam, how was your day?” Draco Starwing said quickly as he pounded the TERMINATE button on the videophone. “How was that event . . . what was it? A debate on who discovered Mercury first . . . or was it a Moon Ball championship?” “The debate was two weeks ago. I lost. Yumi plays Moon Ball. His championship is in two weeks. He’ll probably lose too . . .” “Oh, that’s fab!” exclaimed Draco, having not heard a word Cassie had said. “Now, Cass, I gotta tell ya something. Your mom got a grant to go get her hands dirty and learn about the third-world areas in Saturn . . . so she’ll be going away for a month or so. And I’ll be at a forum on Jupiter for the next two weeks, so that means you’ll be here with your darling bros, won’t that be fun?” Cassie felt her face grow hot. She hated her life sometimes—her parents never home, her brothers endlessly annoying her, and now her own birthday was ignored. She stalked away from her father and headed up the curving DNA-like stairs. Right before she reached the second level, she swung around on her heels. “Aren’t you forgetting something?” Cassie asked quietly, her face twisted into a sarcastic smile. “Cass, whadaya mean? We’ve got it all set up, a student from Neptune is studying here and she’ll live with you guys for a month to take care of you. The school knows, the government knows, your brothers know. Your grandmother knows. What’s missing?” “A happy birthday.” And with that, Cassie dashed up to the seventh story. The next day, in the wee hours of the morning, Cassie heard the vr-vrooming noise of her parents’ space pods zooming away, one to the right, one to the left. Throughout the night they had tried to come in and apologize, but Cassie would pretend to be asleep. Finally, an hour before they left, Cassie’s mother simply came in and placed a parcel on Cassie’s Holovision. Cassie woke up at exactly nine o’clock. It was the first day of Daybreak, the three days of freedom that came after every eight days of work and school. She turned off her floating bed as she hobbled to her mirror, her back sore. Cassie stared at her reflection. She had fallen asleep in her academy uniform. All I see is a short girl in a purple-and-white outfit. Long, stringy dark hair. My father’s big green eyes, my mother’s broad smile. No one even knows my name. Ha, but maybe that will all change, now that I’m thirteen—if they even remember. She moped into the shower and emerged eight minutes later. She changed into one of her comfiest outfits—a silver shirt with fleecy black pants. Now she was prepared to meet the housekeeper. “Oooh, wet hair, did wittle baby Cryeoweepa have a bad night?” Pisces, her fourteen-year-old brother on his way to the kitchen, ambushed Cassie. Only a year older than she, Pisces was Cassie’s biggest annoyance. Her other brothers had a more seldom and subdued teasing style, but Pisces did not pick up on the trend. “Heavens, Cass, you’re what? Thirteen now? And you still act like a baby. Mom and Dad just forgot. Oh, yeah, by the way, they couldn’t find a good present at such short notice, so Dad got you a Starwing Rockets shirt. Have a great one.” And with that, Pisces was on the run again, toward the kitchen. “Oooh, you must be . . . uh . . . Kwasseo- no. . . no . . . Caspian? Ugh, I’ve taken Earthen for several years and still I cannot pronounce the simplest of names. But, no worries, I am Daviana, your housekeeper. I go to school in Neptune where I study Earth, but I wanted to come here and learn about an average family on Earth. At the University of Neptune, all they teach is history

The Best Thing in the World

The late August sun warms the carpet in my room. I sit listening to the sounds below me. Mom and Grandma cooking food in the kitchen. Dad putting the finishing touches on the cake Aunts, uncles, cousins, friends ringing the doorbell My brother running to the door with hellos Loud laughter sounds throughout the house Squeals of delight from baby Maddy’s discoveries “Come down Craig, you’re being rude,” yells Mom. It’s my birthday, I’m not being rude. I’m thanking God for the best thing in the world. The best thing in the world is this moment in my life. Craig Shepard, 12Camillus, New York

Basketball Season

I roll down the car window. It’s hot. The engine murmurs steadily. I can feel my stomach flipping as we near Fullor. The basketball courts loom ahead, all empty but one. The two-door Toyota stops. Amy jumps out quickly. I take my time, slowly stepping out onto the scorched cracked blacktop. I can feel the heat through my black sandals. We wave good-bye, and I force a smile. Inside I am whimpering. Amy jogs over in her running shoes, short brown hair tied back. A blue sweatshirt casually blends into relatively baggy jeans. I wobble after her, my shoes slowing me down. I had curled my hair the night before. It lay like a doll’s. Big hoops dangle from my ears, giving way to a silver choker necklace. It was all planned out the night before. The clothes. I wanted to make a good first impression. Tight jeans match with my tank. It reads “Princess.” We stop in front of the coach. He frowns at me, observing my ensemble. I can feel my face turn red. I didn’t know they would all be boys. Sixteen boys. Sixteen pairs of eyes. Sixteen smirks. But now, as I look around me . . . I just don’t belong We need to run a warm-up lap around the bare field. The boys gradually pass me. Sympathetically, Amy matches my slow pace. I stare longingly in the direction of home, but am forced to turn a corner and head for the sneering crowd instead. A ball rolls out toward me, slowly. I pick it up. What am I doing here? Who am I trying to fool? Being on a team seemed like a great idea two weeks ago when I applied. But now, as I look around me . . . I just don’t belong . . . I close my eyes, in hope that I can just wake up from this bad dream . . . They open, looking down. I hold in my hands a basketball. I drop it, watching it roll away. Slowly, I turn to run. We both slip on the gravel. The boys make no attempt to muffle a loud laugh. I know they’re laughing at me. Amy goes to Felton Junior High. Fullor and Felton are like brothers. The two schools end in the same high school. They accept Amy as one of them. I am the outsider at Remdon Private Middle School. I arrive last, panting loudly. Everybody stares at me, annoyed. I held back the group. Coach says something about an all-star team. “The judges will choose the two best players . . . It’s in your hands . . . Only those who really want it . . .” I am not listening. A boy with mousy brown hair and large front teeth whispers something to his friend. Distinctly I can make out the words “pathetic” and “blondie.” They snicker, causing the coach to clear his throat loudly in their direction. I stare down at my feet. The private whimpers inside of me are threatening to reveal themselves to the world. The only pathetic blond here is me. WEEK TWO I feel my forehead. It seems fine. I stand still and close my eyes, searching every inch of my body for any sign of pain or illness. If I concentrate really hard, I can almost feel some pressure in my head . . . It’s useless. Unfortunately, it seems I’m in perfect health, and basketball practice starts in fifteen minutes. WEEK THREE I don’t know if it is the boys’ taunts or really just my lack of ability that is causing me to miss. Every shot. Insults are murmured constantly in my direction, loud enough for me to hear, yet concealed from the coach. Things like “princess” and “loser.” I don’t dare tell him, for fear of what the rest might do to me. It doesn’t make the situation any easier to accept, that apart from Amy, I am the oldest. No matter how much older I am than the boys, I’m still too young to have a nervous breakdown, but I fear it is edging close. Sobs echo throughout the inside of my head. My life is turning into a living nightmare. Amy gave up trying to convince me to ignore them. Ignore them? How can I just ignore them? Easy for her to say; feet don’t stick out in attempts to trip her as she walks by. Every little mistake of hers is forgotten automatically. Mine are as good as posted for public viewing. WEEK FOUR Shoot . . . miss. Shoot . . . miss. Shoot . . . miss. WEEK FIVE The boy with the big teeth goes by: C.J. Every now and then I make a shot. Nobody notices. WEEK SIX C.J. says he’ll give me a dollar for every shot I make. He coughs when I’m about to shoot and makes attempts to trip me when Coach isn’t looking. So why don’t I just leave? I thought about it. It’s too late. If I go now, C.J. will think he defeated me. I feel like Hamlet. To leave or not to leave . . . I’m not the quiet accepting type. I’m proud. Perhaps too proud. I shout back the first insults that come into my head. C.J. and his followers can top anything I say. I don’t care what the coach thinks, either. I don’t think he even notices anything is wrong. He’s far too ignorant and absorbed in his own little world. C.J. says something about my school. I throw the ball so hard at him, he falls over backward. Coach sees this as an accident. With their “chief” gone for the day, the boys don’t seem to find any pleasure in making my life miserable. Only a fraction continue to taunt me. Today I made my first three-pointer. WEEK SEVEN I am wearing sports pants today. My hair is