Jiraporn looked up. Mother was approaching, shaking her head. “Bad news, Little Mango Tree. I talked to Bouchar. He says we lose the house unless we pay the remaining mortgage in one month.” “But so much money!” Jiraporn protested, hugging herself. “We can’t harvest enough rice to pay that, let alone feed ourselves and the spirits.” Mother nodded dismally, and sat down next to Jiraporn. Gently, she pried the knife and half-peeled, slightly ripe mango from her daughter’s fingers. “I don’t like to see you with a knife, Jiraporn. You might cut yourself.” Jiraporn’s soft, dark eyes restlessly watched her mother’s hands wield the knife, sliding the dull, silvery blade across the scarlet-gold fruit in a peeling motion. “But Mother, I must help somehow. You let Vichai work the plow.” “Well, he is much older than you,” Mother stated primly. Vichai was seventeen, three years older than Jiraporn. She paused a moment in her peeling, then stood abruptly and strode away across the smooth dirt. “Go work on your math homework, dear,” she added over her shoulder. Jiraporn’s eyes grew moist and shiny, and she clenched her fingers in her loose black hair. Yes, she could go do her algebra while her whole family starved and lost their house and rice field. She tilted back her head and looked up into the shady branches of the kiwi tree. “But I would rather die than be idle and useless,” she murmured to their rustling, sunlit leaves. A cicada chirped nearby, and a large cricket alighted on her navy blue skirt to rub its silken wings. “Next,” Jiraporn confided to the cricket, “she’ll be locking me inside.” Jiraporn’s eyes grew moist and shiny, and she clenched her fingers in her loose black hair Sighing, Jiraporn stood up, brushed off her clothes, and hopped onto her brother Vichai’s bicycle. Pedaling with her feet, she gripped the handlebars and steered it over the dirt in front of her house to the narrow path that led to the market. The wheels spun slowly, bumping over loose stones and gravel, jostling Jiraporn from side to side. Yet she was relaxed and confident. It was not the first time she had taken her brother’s bike while he was away in the fields. And she had pinned a note to a banana tree so her mother wouldn’t worry any more than she always did. “Jiraporn!” Visit exclaimed when she pulled up beside his stand and got off her bike. He grinned. “Off on your own again?” Jiraporn shrugged. “I need help, I guess. What are you selling today?” she asked suddenly, avoiding the subject. “Scallops?” “Nah, carp. Got the best here in all of Thailand.” He gestured to the wooden bins of fish. “You must really be distracted to mistake carp for scallops.” “So I’m blind,” she said carelessly. “Just one more thing to worry about.” There was a brief silence and a man walked by, selling cotton and banana bunches. At last she said heavily, “The truth is, Visit, Bouchar is taking our house away if we don’t pay by next month. We promised two months ago to pay, but we just don’t have that much money.” Visit’s wrinkled face was grim. “Nasty landlord. How much?” She told him. “I need a plan. A good one. I do all this schoolwork that’s supposed to make me smart since Mother won’t let me work, and now I have a chance to put it to use and I can’t think!” Jiraporn buried her face in the white cotton sleeve of her blouse. Visit sighed and patted her back. “Maybe I can cheer you up. It’s not much, but . . .” he wrapped two fish in some greasy brown paper. “Take this home to your mother. By the way, that Anna Kuankaew came by the other day.” Jiraporn nodded absently, stuffing the fish into a wicker basket nailed to the bike’s handlebars. Anna Kuankaew was a rich lady who had come by once, wanting to buy their mango tree, but Jiraporn wasn’t really interested. “Thank you!” she said with sincerity, pedaling off. “Wish I could help!” Visit called after her. “It’s outrageous!” exclaimed Mother in anguish when Jiraporn slipped quietly into the kitchen. Mother set a dish of steamed rice and prawns on the table and put her hands on her hips. Jiraporn stood, still and solemn, for a moment before going to place the parcel of fish on the table. “Explain yourself,” Mother commanded angrily. “How dare you ride a bike, you could have been overturned and died!” Calmly, Jiraporn said, “Visit gave us some fish.” “Take it back,” snapped Mother. “I’ll not be accepting charity.” “It’s not charity, Mother,” put in Vichai from the corner, sitting down cautiously on a low stool, “it’s a gift.” Shaking her head, Mother sighed and placed a pitcher of coconut milk and some sliced mango beside the prawns and rice. Seating herself, Jiraporn poured coconut milk into her cup and put food on her plate. They ate glumly, in silence, except for one point when Mother, wiping her mouth on her apron, muttered, “If your father was alive everything would be fine.” Lying on her mat that night, staring at the filmy gray mosquito netting that floated beneath the dimly burning lantern, Jiraporn wondered sleepily what it was like to make a difference. The next morning was hot, and Jiraporn opened the door to let some fresh air in as she cooked a simple noodle soup with mushrooms. Mother entered with an armful of bananas. “Sorry about yesterday, Little Mango Tree. I ‘spect it’s on account of that money.” She dabbed at red eyes and sniffed. “‘Fraid I cried a great deal last night.” Dropping her spoon, Jiraporn bent over and comforted her mother, hugging her. At least that was one thing she could do. As she drew back, Mother set the bananas down and started making tea. After a moment, Jiraporn begged, “Please let me harvest rice, Mother.” Mother

May/June 2002

Patches of Sky Blue

When my mother died the summer I graduated seventh grade, the first thing I did after silently returning home from her funeral with my father was dig through my trash bin in search of a previously ignored leaflet distributed by our local Parks and Recreation. I then signed myself up for every class, workshop and camp they had listed. If my father was mystified or annoyed by my actions, he kept it to himself. Perhaps he was so overwhelmed by his own grief that it didn’t strike him as odd at the time. I also plastered my bedroom walls with the activity schedules for each class until there wasn’t a square inch of wall that wasn’t completely covered. It became an obsession. I attended each class religiously, never missing a beat. It took me from sunup to sundown every day and gave me a reason to get out of bed in the morning. I stayed up late into each night working on this or that small class project. The classes I took covered a whole range, from kayaking to keyboard to cheerleading to modeling. In art I painted pictures of daisies and smiling fairies. I wrote poems in a kind of singsong rhythm about balloons and happy cows. There was nothing I was doing that even hinted at my loss. Something would have to break me and my newly focussed life because it was all an act. I lived like an actor who can’t get out of character and leads a kind of half-life. No one seemed to understand me anymore, myself least of all. “Elle, you’ve never had trouble getting started. Why the exception today?” It happened in poetry class. I had been just about to hunker down for another three-hour session, and had a particularly sugary first line in mind when Mrs. Tucker, the instructor, made an announcement. “Today we’re going to have a special assignment, we’re going to write about some things that make us sad. Any examples?” She looked around cheerfully, her watery blue eyes slightly magnified by rectangular glasses. She was the typical well-meaning but clueless teacher. She didn’t seem to see the irony in her merry expression as she repeated the assignment: “Write about something that makes you sad” . . . smile . . . something that makes you sad . . . She had started to pass out the papers when I asked numbly if I could be excused to go to the bathroom. She smiled. “Yes, you may.” I slipped out the door into the main hall of the YLC or youth learning center where the class was held. I didn’t go to the rest room, though. I just leaned against the wall and stared at the ceiling. I had been there longer than I had thought because suddenly my teacher was there, bending over me, and looking anxious. “Elle, are you all right? I thought you were just going to the bathroom . . .” She looked at me as though expecting an answer; an answer to what? Did she think I knew every little thing about myself?!? Wait, I was being stupid. This was a simple question. The answer wasn’t simple but at least I could give the answer she was expecting to receive. “Yes, I’m fine,” I said. “Good.” She looked satisfied as I followed back to the classroom, noting how her walk resembled that of a duck’s. Ducks seemed like a good subject for a poem. Then I remembered. My assignment was to write a poem about something sad. Instead of writing, I drew a cartoon-like duck wearing a purple vest (not unlike the one she had on). Then I sketched a cartoon of the actual Mrs. Tucker. Mrs. Tucker wandered aimlessly around the room, every so often saying things like “Good job!” and “A nice beginning.” Even when she criticized, she beamed as though she were saying something nice. When she stopped by my desk, her smile flickered and she drew her penciled eyebrows together in a look that might have been annoyance if she hadn’t maintained a partial smile. “Elle, you’ve never had trouble getting started. Why the exception today?” How could I answer that? “Ummm,” she peered closer at me, “yes . . .” “It’s. . . hard,” I offered thickly. She relaxed her expression and sighed. “You should have said you were having trouble, I could have helped you sooner.” She got down on her knees so her face was level with mine. “Write down five things that make you sad,” she said. “I don’t know.” “I’m sure you can think of something; everyone is sad sometimes.” “Not me.” After I said this I realized both how childish it sounded and how utterly untrue it was, but I kept my mouth closed. “It’s not a bad thing. Everyone . . .” I cut her off. “I said nothing makes me sad, and I mean it, OK??” She suddenly became uncharacteristically crisp. “I don’t believe it. You were sad when you forgot to do your homework that one day. You said, ‘Mrs. Tucker, I’m very sad that I forgot my homework.’ You said it, I heard you! I rememb- . . .” Then it burst. All the fury and fear and grief and even guilt that had been silently smoldering inside me these past months burst. “Do you think that’s what real sadness is?!?” She looked taken aback. “Well, I . . .” “Do you??” My voice rose to a pitch. The other students started turning on me, looking annoyed, and alarmed and even . . . sad. Suddenly my pen flew to the paper and my hand started scribbling down words faster than my mind could take them in. I wrote about metal screeching against metal, muffled screaming, flashing red light reflected on water-drenched pavement, dark silhouettes being carried past on stretchers. Then there was fluorescent light shining on bare white walls. A naked light bulb, bathing everything in a blinding glow.

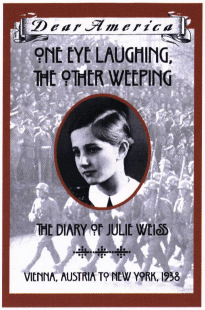

One Eye Laughing, the Other Weeping: The Diary of Julie Weiss

One Eye Laughing, the Other Weeping: The Diary of Julie Weiss by Barry Denenberg; Scholastic, Inc.: New York, 2000; $12.95 When someone says the word “Jewish” do you feel a sudden rush of hate, a thrill of fear, or does it even stand out enough that it makes you feel anything at all? For Julie Weiss, a Jewish girl who is about twelve years of age, that word means fear and confusion. One Eye Laughing, the Other Weeping is a book about the Holocaust. A book about the astounding measures the Nazis took while trying to banish the Jewish culture. Julie experiences the horrors of the Nazis, firsthand. This author does an amazing job of creating a young girl that is just like the children today. Julie worries about growing up, making friends and going to school. But then one day her world is shattered. The Nazis take over Vienna and suddenly there is more to her life than just fun and games. Now, she has to worry about whether or not her life and her family’s lives are in danger. Friends turn into enemies and respect turns to hatred. The Nazis chant in the street, “Kill the Jews, kill the Jews!” Is it possible that they could kill Julie? Julie is immensely confused. Why is it that suddenly Jews are thought to be terrible monsters instead of just human beings? Before Hitler had entered Julie’s life she hadn’t thought anything of her religion. Her family never went to the synagogue, never prayed and never thought very much about God at all. So, why is it that suddenly she is thought to be this disgusting thing that everyone hates? Could it be that the only reason that she is considered Jewish is because Hitler says she is? This book is portrayed to you in fascinating diary entries. One night Julie writes about when the Nazis barge into her home. As the Nazis go through her family’s house, throwing things out of windows and destroying everything in sight, Julie sits silently in fear. Then, suddenly her brother and father are yanked out of the house. Outside, they are forced to scrub the sidewalk to rid it of anti-Hitler signs. Eventually, the men and boys realize that the liquid they are scrubbing the sidewalk with is not water, but a kind of paint stripper that burns their hands. If they stop scrubbing they are punished severely. Many other events like that one are referred to in the book. One man who refused to do as the Nazis ordered had gasoline poured over him. Then, they lit a match and as the man protested and screamed that he would do anything the Nazis wanted, he was burned to death. The author, Barry Denenberg, tells the truth, plain and simple. Although I cried at many times throughout this book I am glad that I have finally found a children’s book that tells the unvarnished truth. One Eye Laughing, the Other Weeping will tell you what really happened in those years so long ago. It will not hide the story behind curtains of lies. I have read many books about the Holocaust, but none were quite as moving as this one. Thankfully, I have never experienced the constant fear that Julie must have lived with every day, but when three buildings were attacked by terrorists in the United States I experienced as much fear as I have ever felt in my entire life. Though no one I knew was hurt or killed there, the thought of all those who were chills me to this very day. The fear that most American citizens felt on September 11, 2001 was a small taste of what so many people who lived during the Holocaust had to survive with day in and day out. As Barry Denenberg weaves history and the life of an ordinary girl together, this story comes alive. Suddenly, you’re reading much more than the diary of an ordinary, young girl. You’re reading a book about human cruelty and human kindness. You’re reading a book about something real that may have happened to your ancestors. Read this book to find out what will win in Julie’s story, evilness or goodness? Cassy Charyn, 11Bainbridge Island, Washington