I step out into the clouded dusk the dark light pushes up against my skin the steady contribution of frog song pours into the air, making the measuring cup of the night overflow. the rock is cold beneath me, reminds me to shiver. the last light swiftly falls underneath the trees and I capture it in angular lines on this paper. the air grows darker and huddles nearer. stirs, exhales in one gust of breath, anticipates the night. the last strip of gold is disappearing and here, on the outskirts of the sanctuary of the porch light, my shadow is huge on the ground. slapped across my page, the dark mimic of my pencil waves. now the sun remains only as a half-inch-wide ribbon of dull orange beyond the trees and the frogs announce the sun will set tomorrow, too. but I am hunched here on the edge of the world, and the sun just fell off. Nicole Guenther, 13 Vancouver, Washington

May/June 2005

My Piano

I sit at my piano. It lies in my family’s living room, covered in dust. Not the neglected type of dust, but the vintage, rustic type of dust, the dust that gives the piano a cozy, charming feeling. I run my fingers over the old white keys. Now I run my hand over the old chestnut top, getting a handful of dust. Rain knocks at the windows and I can hear Kelsey crying in her crib. Kelsey is my baby sister. I do get jealous of her, but I can do something she can’t; play the piano. I open the parchment pages of my music book and, all at once, my fingers fly. Dancing on their ivory carpet, my fingertips can’t stop and there is no need for my music book, but I can’t tear my hands away from the piano to take it down. I’m flying, soaring, away from Kelsey’s crying, the pounding of the rain, the rustling of the angry trees outside. All I can hear is the sweet hum of my piano’s breath, and I can almost imagine myself in a white-and-black- checkerboard room, with only me and my piano. And now my prancing fingers, cantering across the creamy white road, like ten brown horses, pulling the purple carriage of my sweater sleeve, have come to their destination. The black notes are gone from the paper, the song has ended. I rest my hands and breathe in the smell of the dust that has risen from the movement of my ten steeds, pounding the road, leaving tiny footprints of dust. I sigh, and carefully rum the pages of my music book, preparing for my next routine. Slowly, I place my hands on the board, and suddenly, there are no hands, but two fluttering tan sparrows. Their little calls match with the sighs of my piano, and again all I can hear is the singing from the chestnut base. The sparrows flutter from key to key, without any movement; just sweet, free flight. This song is shorter than the first, and my birds land soon, landing by the edge of my denim jean lake. I would’ve started another journey to that checkerboard room, my fingertips ready to turn yet another page in my music, but Momma comes in, Kelsey in her arms, wrapped up in her little pink Polartec babysuit. Obviously, Daddy has already announced that I am going to play, because the audience claps loudly Momma smiles and says to me, “That was good practicing, Brandi. I heard you from Kelsey’s nursery Do you want to take a walk with us?” “You’re taking Kelsey out in this rain?” I ask. Momma nods and says with exasperation, “I can’t get her to sleep, so I’m hoping maybe a walk will tire her out. Are you coming?” I nod and pull on my coat, boots, and scarf. Then, I run to get my umbrella. Passing the living room, I silently bid my old piano goodbye, and my toffee-colored horses crawl back into their fleece stables, my pockets, and rest. My piano is my friend. The piano is not my only friend. My best friend is Paula Leigh, although I just call her Paul, like everyone calls me Brandi, even though my real name is Brianna May. Momma and Daddy named me that because Daddy liked the name Brie and Momma liked May, and they both liked Anna. So my name is actually three combined. Anyway, Paul is my best friend, and also my neighbor. She’s three years older than me, but we’re like sisters. Sometimes she chaffs my love of piano, especially when we can’t play because of practice. I don’t mind though, because I can razz Paul about her love for trumpet, and she practices just as much as I do. We are friends because we both understand each other’s love for music. We both know how important music can be, to two kids like us, at least. The piano is my key to friendship. After Momma, Kelsey, and I are home from our walk, it is 11:12. Kelsey is asleep. After Momma puts her in her crib, she asks me if I want to go shopping with her. “No,” I say as I pour myself a glass of orange juice. She just smiles and says, “Too bad, hon. You have to come. It’s for a surprise.” So I put on my coat, hat, scarf, and boots again and we go into the car. Momma drives us to the mall and she leads me inside. “What’s the surprise?” I ask, for I love surprises. Momma smiles again and shakes her head. Finally, we stop in front of a little shop that says Dresses and Suits for the Little Folk. We go here every year to get a Christmas dress for me, and now Kelsey. I know this is only part of the surprise. When I follow Momma in, I see frills and bows and frou-frous. Two tall, chattering ladies come over immediately. They talk so fast that I cannot understand them. Eventually, they lead Momma and me to a tiny dressing room. It is amazing that we can all fit. One woman has a pile of dresses in her hands, and the other has a hairbrush, a mirror, and a pile of hair ribbons. Now the ladies pull off my sweater and my pants. I stand there in my underwear and undershirt, and I feel like a doll. The two woman are pulling dresses over my head, and then pulling them off. I’m so glad when they leave, that I don’t even see what dress they are ringing up. Momma smiles and says, “Well, as soon as we get the dress, I can tell you what your surprise is!” So we go up front and the ladies hand us the dress. As soon as we get out of the store, I pounce on Momma, “What’s the surprise?! The surprise?!!” Momma smiles knowingly and says, “You’re going to

Roses on the Water

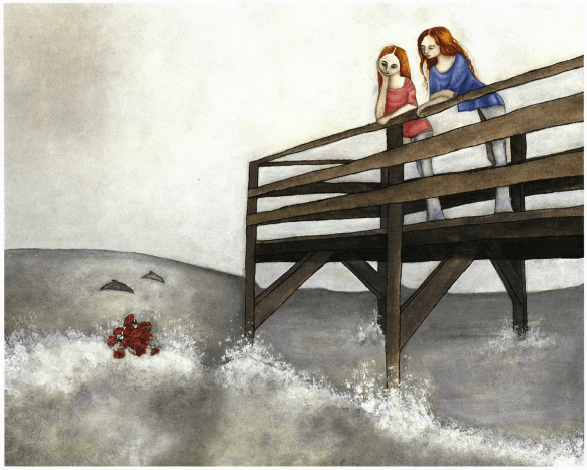

Two girls were walking along, in sweatshirts, jeans and flip-flops, discussing the meaning of life. “. . . now, lip gloss needs to be applied liberally, every few hours or so. Do you think this eye shadow is too bright? Omigosh, I saw the cutest pair of jeans in that shop. Are those new earrings?” I didn’t answer my friend, just basked in her flow of words and the sea breeze blowing in from the west, glad that it wasn’t freezing, raining, or both. Having both finished a giant essay, we were ready to enjoy what remained of the Sunday afternoon, walking down to the beach for some ice cream from the Creamery. A seagull flew overhead, a splash of white against the gray sky. “What d’you think, Kate?” asked Meg. “Mm. What? Oh, right. You should go with the pink,” I answered. Thunk-skip, swish, thunk-skip swish, two pairs of flip-flops flopping against the pavement. We walked down the waterfront and to the pier, planning to visit the aquarium and our favorite shark, Rosie, who was approximately three centuries old and counting. The bell over the door tinkled softly as we went in. Meg headed straight toward the touch tank. She scooped up Pickle, the sea cucumber, and planted a large kiss on him. I stared. “You know, if you wanted to kiss something that badly, I’m sure Willy would be happy to oblige.” Meg sighed. “It’s not for that, stupid. Sea cucumbers are for good luck. I need all the help I can get. That final on the Renaissance is next week!” “Oh. OK then.” I hesitantly brushed my lips against Piclde’s slimy back, smelling salt water. I gently put him back in the water. Pickle, being rather intelligent for a sea cucumber, started squirming away, as fast as any sea cucumber could, from the edge of the tank. Next, we went to the shark tank, amused at the little five-year-old who was putting his hand against the tank until a shark swam under it, and running away, shrieking with delight, then coining back to do it again. “Hello, Rosie,” said Meg, addressing a rather stately-looking shark in the back, who was looking, I could’ve sworn, irritably at the five-year-old. We drifted from tank to tank, observing the stately sharks, elegant anemones, and courageous crabs battling with their large claws. Things were mostly quiet except for the hum of the water pumps. The air smelled like old seaweed and a fish market. Over to my right a large fish surged forward to nab that last chunk of fish food before it settled at the bottom, to be eaten by the little mollusks that were employed for just that purpose; their role in life to simply clean up after these giant, messy eaters who left their scraps lying around to be picked up by smaller beings on the food chain. Sure enough, the gluttonous fish had dropped some of its snack, and, sure enough, a competent-looking snail wandered to the spot to clean up. Keep going, little snail. It’s your turn for dinner, I thought. The snail’s pearly white shell moved forward, ambling along at its own place, having no need to rush. Outside, the breeze picked up. A gust of cold air swept through the roundhouse, startling me. I stepped back, stepping on Meg’s foot. “Hey! Watch it!” She poked me. “Let’s get out of here; there might be dolphins out. Besides,” she wrinkled her nose, “it smells like cat food in here.” So we left the aquarium, leaving our Piscean acquaintances, to walk on the pier. A wave hit the stone pillar, making the whole jetty sway. Sea spray hit my face, salty and sweet at the same time. Meg was scanning the horizon, looking for the gray shadow and splash of white that signaled a dolphin pod. She grinned and nudged me. Where? Oh, right, over there. The dolphins leapt over the waves, too far out to swim, but close enough to view from the pier. A foolhardy surfer was getting ready to try and ride a huge wave. I shivered; that wave was huge, and it was not exactly warm on land, so it must have been freezing in the Pacific Ocean. Red? What was red doing among the grays and tans, greens and blues, of the beach? The surfer was successful, turning his board skillfully, yet compared with the dolphins he looked rather stupid, depending on a piece of fiberglass, while the dolphins managed well enough with what they already had. Still, it was an admirable effort, and the surfer was almost to land before he fell off spectacularly, right into the sand. Meg and I started laughing. I looked out to the west, and saw a flash of red. Red? What was red doing among the grays and tans, greens and blues, of the beach? I leaned out over the railing, and saw that the red was actually a bundle of roses, drifting along on the current. Meg had noticed it too. We stood, looking for a long time, as it floated away And that day, though what was actually required for an education had been completed, I learned something: Even among an ancient shark, two girls, the ocean, and a surfer, there is something that breaks the pattern, some slight inconsistency. Red roses from someone’s beautiful garden, maybe from some greenhouse in Indiana, can end up floating on the Pacific Ocean. And that makes me wonder, sometimes, if writing new words, changing the tune, or breaking the pattern can be a good thing after all. Katie Sinclair, 13Manhattan Beach, California Thea Green, 13Marshall, Virginia